The long sweep of Gerrans Bay, with its high vantage points at the Nare Head and St. Anthony made it an ideal location for the “moonlight traders”. With a number of easily reached covers and no end of deep “drangs” wide enough to take the small boats used for landing the contraband, the smugglers of Gerrans Bay were more often than not one up on the revenue officers who were sent here to stamp out the “free trade”. And with underground passages leading from the beach to the outlying farms and a hundred and one places of concealment, it must have been an endless game of cat and mouse.

In 1753 Rear Admiral Sir Richard Spry of St. Anthony in Roseland who had been ordered to search for smugglers between the Isle of Wight, the Channel Islands and the Lizard, wrote to the Secretary of the Admiralty and stated: “I am credibly informed by Gentlemen in the neighbourhood that there are upwards of fifty sloops and boats that go yearly to France from the adjoining Parishes of Veryan, Gerrans and St. Anthony.”

Out witting the authorities became a fine art but the tables could just as easily be turned, as was the case when the preventive men rowed quietly up Froe creek and carried their gig across the narrow strip of land which divides the parishes of Gerrans and St. Anthony in Roseland, so enabling them to launch a surprise attack on the smugglers working in Gerrans Bay and also on their watchers on the headland.

Among the registered deaths for the parish of Gerrans in 1782 are two entries where the cause of death is given as “found dead on her bed supposed by drinking brandy”, and “‘found dead with drinking brandy at Portscatho”.

The lighting of fires on the cliffs was a way of guiding the returning boats to a safe haven, and certainly went on at Gerrans as it is recorded that in November of 1822 George Sawle along with James and Francis Penver were caught in the act and were sent to Bodmin gaol.

The West Briton reported in 1816 that a revenue cutter off Gerrans bay had given chase to a suspect vessel. Thinking that the game was up the smugglers threw the greater part of their cargo, consisting of kegs of spirits over the side. Some days later three local men, George Buckland, Thomas Pascoe and William Tregidion took their boat out to try and recover some of the goods. Unfortunately the boat was upset by a sudden squall and all three were drowned.

But old habits die hard and several local families still tell the tale of how their great grandfathers used to row across the Channel and return fully laden. One night in the late eighteen hundreds the revenue men arrived at Parkenvrane Farm in Gerrans where the Sawle family lived and began to search for contraband. They searched each room in turn without success. When they came to one of the bedrooms however Mr. Sawle stopped them and explained that they could not search that room because it was occupied by a lady who was just about to give birth. The gentlemen of the customs said that they would settle for a quick look. On opening the door all they could see in the dimly lit room was the form of a very pregnant woman lying in the bed and so they left empty handed. The shape in the bed was nothing more than a bundle of clothes and a barrel of French brandy. Perfume, silk, salt and even playing cards all went to make up these illicit cargoes, but brandy seems to have been a favourite here abouts. One old lady told me how the customs men paid her grandparents a visit and were invited to stay for tea which they gratefully accepted. Little did they know, as they sat at the table enjoying their clotted cream that under the long skirts of the lady of the house was secreted a barrel of brandy.

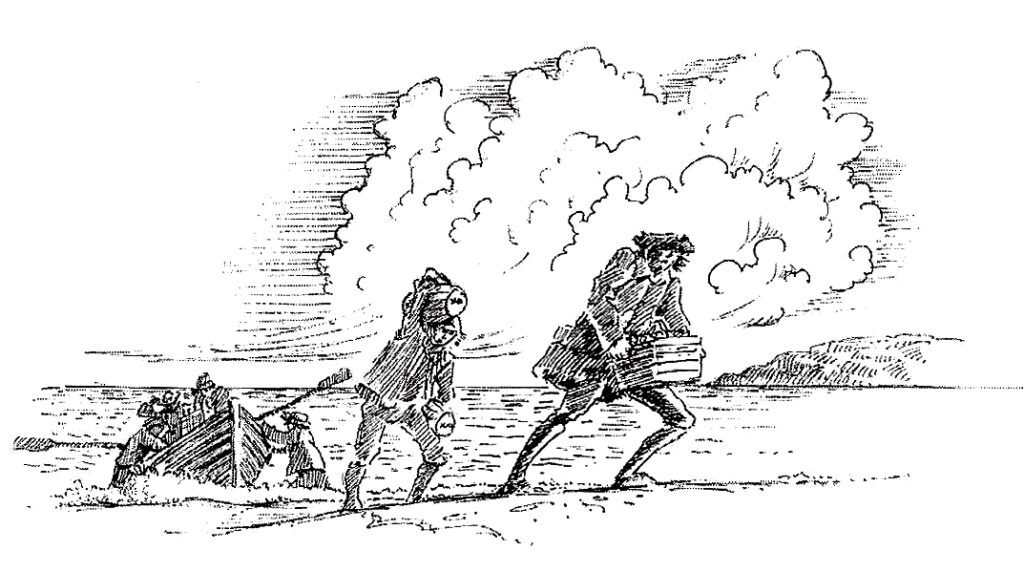

As recently as twenty years ago one old local recalled how his great grandfather used to go across to France. ” They used to leave here in a 12-oared gig, said my granny. They’d be gone a fortnight. They used to have some rough times; sometimes she said, we used to think they was never coming back. The squires used to finance the lot, and they used to take the silk, and of course the others used to take the brandy. They used to go across country with the donkeys with it on their backs, to the different inns to sell it. They never kept to the road. Some of these old bridle paths are smugglers paths.”

In 1804 The Royal Cornwall Gazette revealed: “His Majesty’s armed cutter Arthur lost a six oared boat from her stern, on Thursday the 27th September, which drifted ashore near Gerrans and was destroyed by per-sons belonging to that place. Whoever will give information to Captain Kinsman, so that the party may be brought to punishment, shall on conviction, receive the reward of five guineas.” There seems to be no record of a conviction – honour amongst thieves perhaps.

But we in this time should not be to quick to judge. Luxuries were few and wages a mere pittance. French brandy could be obtained in its native country for as little as five shillings a gallon and sold at home for up to five times that amount and no doubt the heavy risks that these people took were, they felt, well rewarded.