The Cornish industrial landscape is coming under increasing scrutiny. Interest in all things connected to Cornish mining and other aspects of the county’s industrial past has really taken off during the last couple of decades. Formerly great mines like Dolcoath, Fowey Consols, Levant, Ding Dong and Devon Great Consols have become household names, and the mine enginehouses of the Tamar Valley, Bassett Mines, Wheal Uny and Botallack have become well known through magazine photographs, post cards and TV serials. There has been an avalanche of books, booklets and articles on all facets of mining history since the 1960s, when the Bradford Barton mining history books first began to appear. But, there are whole periods of the Cornish tin industry which remain obscure and generally hidden from view.

During this unusually dry summer, when the land has been starved of water for a very long period, the terrain has displayed ancient archaeological features perhaps never before noted. Aerial photography has revealed settlement patterns, old fort shapes and early industrial sites on a grand scale.

It is perhaps ironic, that two extremely significant tin sites, which have been dug by professional archaeologists during the recent, often very wet, summers, have been left fallow this past summer. Finance, that dirtiest of all words (alongside the expressions “lack of funds” and “no grant money available at this time”), has meant that the annual digs at Merrivale on Dartmoor, and at Crift Farm, Lanlivery, were cancelled. It is a shame that 1995 provided the ideal conditions for successful and enjoyable digging on these sites.

The story of the Crift Farm site is interesting. Until the mid 1970s there was absolutely no evidence of ancient buildings or anything else to indicate past industrial use. The site lies at the top of a grassy, former arable field. An old Cornish hedge of impressive dimensions passes within 15 feet of the site, which is high up the south-west slope of a hill, not too distant from the once-extensive tin streaming areas of Redmoor. It had been the custom in this and the adjacent fields to plough with the shear set at about 7 inches. A contract farmer inadvertently set the plough at a depth of 9 inches. The result was that a lot of sub-surface rocks were struck by the plough, and, centred on what became the archaeological site, the ground was covered by what appeared to be black glass.

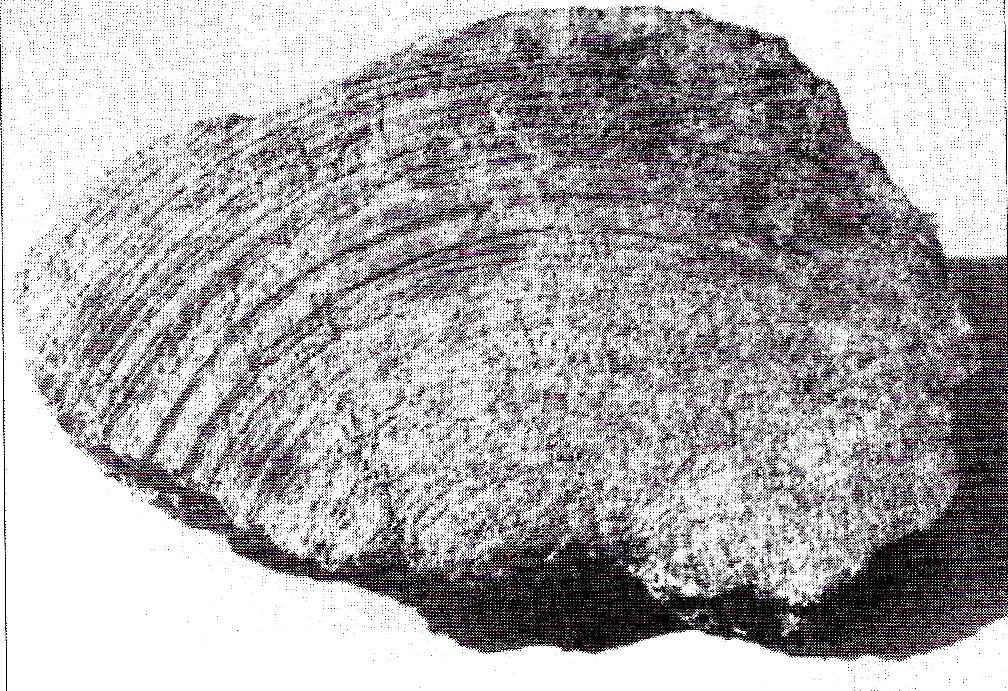

It was hand operated for grinding tin slag for re-smelting. (scanned from CT)

Eric Higgs, the farmer, a keen amateur archaeologist, took some of this “glass” to Truro Museum, where the curator, Mr. Douch, informed him that it appeared to be old tin slag. Attempts to gain the interest of archaeologists failed. The farmer refused to be fobbed off and pursued his inquiries with renewed vigour. In 1984, I was asked to take a look and was amazed at the vast quantity of tin slag on the site. The slag lying on the surface at the centre of the site was considerably more than the total weight of all of the ancient tin slag so far discovered in Cornwall. I took some to the Archaeological Department at Exeter University, where I was told: Yes, it is ancient tin slag…. No they could not tell me anything about it. No they were not particularly interested. My attempts to gain the interest of Cornish based “experts” were no more successful than those of Farmer Higgs. Then I had a lucky break. A year or two later, whilst looking at a tin site in Constantine with Bryan Earl, who has a considerable knowledge of historical metallurgy, I remarked that the site, whilst interesting, was nowhere near as potentially significant as the one at Crift. Bryan went with me to meet Farmer Higgs, and from that meeting things quickly went forward.

The next person to arrive at Crift was professor Ronnie Tylecote, who saw the site’s potential immediately. Under his direction we dug a trench across the site, discovering various stone tools, including an ancient crazing stone, and evidence of an iron working forge. Whole sacks full of tin slag were taken away by the farmer, including clay furnace lining and many other “finds” of varying importance. After eighteen months of weekly digging, photographing (including many aerial photographs from Bryan’s plane), sketching and surveying, we enjoyed our next step forward. Adam Sharpe from the Cornwall Archaeological Unit visited the site and showed great excitement, and he was followed by a party of archaeologists from Turkey and the United States. Dr. Yener, now Professor of Archaeology at Chicago University, was accompanied by several archaeologists who had been digging in Egypt and Turkey. This was followed by a seminar at Camborne School of Mines, which gathered archaeologists from several countries and universities together. The Bradford University contingent, led by Dr. Gerry McDonnel began plans to carry out annual digs at Crift Farm and their continuing work has thrown up some truly interesting results.

The jury is still out on many aspects of the Crift Farm industrial site. However, the central period around which the archaeologists have fixed the working is in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Tin was certainly smelted on the site, having, apparently, been gathered from a wide area. Re-smelting of tin slag is also a very likely use of the site. Iron working took place on the site, either during or after the main tin working period. The shapes of several buildings or rooms have also been discovered by Bradford University, and the size of the original industrial area has grown as the excavation has spread out.

Whatever the archaeologists decide about the original and later uses of the site, and the dates when the workings took place, it is of great significance, that this important link in interpreting our mining and industrial past, which lay concealed for centuries beneath a Cornish farm, is only now known of due to the determined persistence of an enthusiastic amateur. How much more lies hidden in this way? Let us hope that the long, dry summer will have helped reveal some of it!