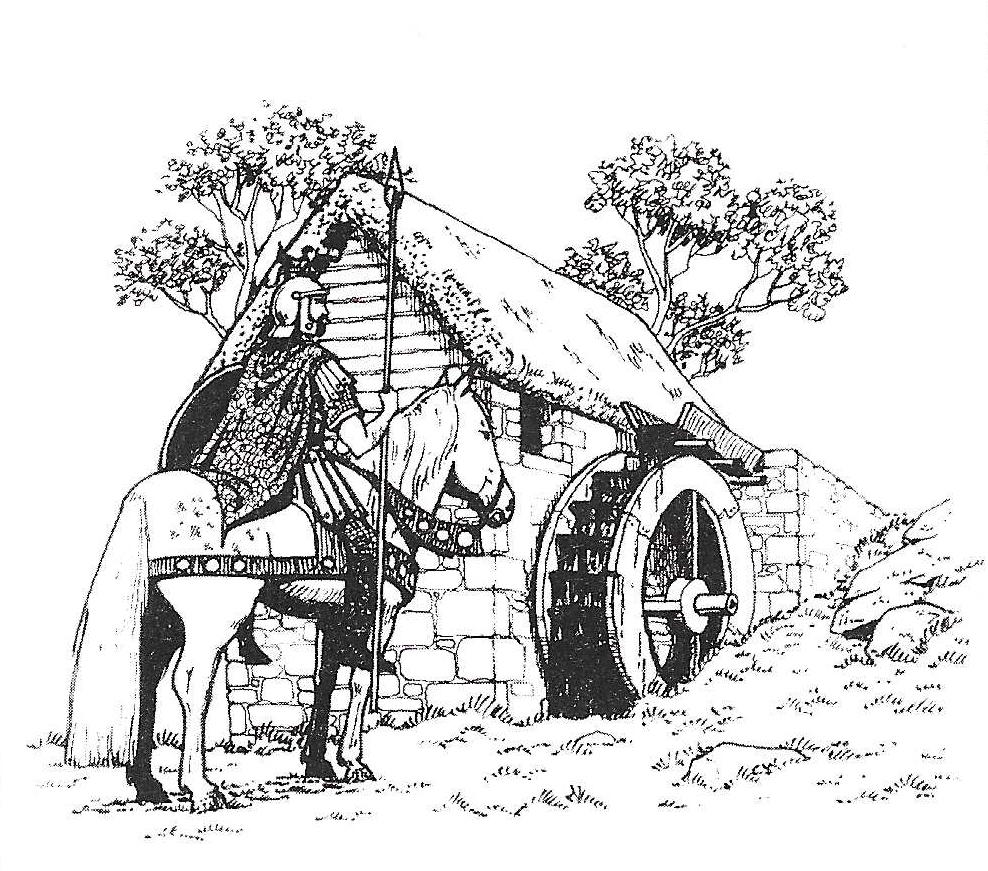

The road from Catchall to St. Buryan twists its way through a valley bottom near a house called Canopus and close to where Trelew Mill once stood. The stream flows on southward, past the site of Trombothick Mill and through one of the most pleasant and unspoilt valleys in West Cornwall towards where it once turned the wheels of Vellandruchar (“tucking/fulling mill”) and Vellansagia (“sifting mill”).

It is hard to imagine that such a peacefully innocent scene, with its green meadows and fine stands of trees, may once have been a site of vicious slaughter and that the long disappeared mill, its site hidden in a boggy grove by the ruins of Vellandruchar Cottage, might once have seen its wheel turned by a blood reddened stream – for this is this site of a legendary Arthurian battle.

How strange that one of the region’s best known tourist centres, just down the road and which claims to tell the area’s “real story” fails to even mention this battle in its Arthurian content, which is limited to a few stray and scarcely relevant quotes from Malory.

The story goes that the “Sea Kings”, often described as “Danes”, mounted an invasion fleet after several unopposed raids on the Land’s End coast. They landed at Gwenver, just north of Sennen Cove, and marched inland. Immediately, the signal fires were lit to raise the alarm, blazing out from each of the beacon hills in turn, up the length of Cornwall and alerting Arthur (always “Prince Arthur” in the Land’s End stories) at Tintagel.

He lost no time and, commanding an army with nine other kings at its head, met the invaders at Vellandruchar, slaughtering them in battle so vicious that the nearby millwheel was worked with blood. Some sources claim that this was Kemyel Mill but, as that is fed by an entirely different stream, it could not have been. After the battle, Arthur’s force rode westward to mop up at Gwenver, only to find that any escape of the invasion ships had been prevented by a wise-woman of Sennen. Her spell consisted of emptying the waters of Sennen holy well (now lost, but thought to have been somewhere near the Old Success Inn) against the hill, and sweeping the church (probably the nearby Chapel Idne, long since destroyed and replaced by a car park) from door to altar. This invoked a west wind which, with the spring tide, drove the ships up onto the beach to where they could not be relaunched. The guards were put to the sword, and the ships left to rot.

After pledging themselves in the holy well, Arthur and the nine kings held their victory feast on the Garrack Zans (“sacred rock”), ever after called the Table-maen. This flat-topped rock still exists, the only survivor of various such stones which stood in the “townplaces” of Sennen and St. Levan parishes. Here, the figure of Merlin appeared and, in his usual cheerful way, was “seized with the prophetic afflatus” (won-derful word!), chanting that: The Northmen wild once more will land and leave their bones on Escalls Sand; The soil of Vellandruchar’s plain again shall take a sanguine stain; And o’er the millwheel roll a flood of Danish mixed with Cornish blood; When thus the vanquished find no tomb, except the dreadful day of doom.

The 18th century historian William Hals was to claim that the meeting around the Table-maen consisted of seven Saxon kings, and took place c.600 AD, a good century after Arthur. Unfortunately, and like many historians of his day, Hals produced more bull than the county of Hereford and, by naming his kings, destroyed his own argument – for they can never have met, at the Table-maen or anywhere else, a point repeatedly missed by modern historians. Cissa of the South Saxons lived a century beforehand and, while the others named flourished in the late 6th and 7th centuries Aethelberht of Kent was dead 16 years before Penda of Mercia came to power. This of course is additional to the fact that, in the year 600, the nearest Saxon controlled area lay a good 200 miles to the west, on the far side of a fiercely defended Celtic kingdom.

But could the Battle of Vellandruchar have actually hap-pened? Clearly, the invading force couldn’t have been Danes, who did not appear as a threatening sea force until 9th century, 300 years after Arthur’s time. They could only have been Saxons but, as in the Arthurian late 5th century Saxon incur-sions was more or less confined to Britain’s east coast (there was no such place as “England” until the 10th century), how could Saxons be harrying the Land’s End coast?

The answer lies in Gaulish and Irish records. At this time, the islands of Loire estuary housed a hefty Saxon pirate base, led by a formidable character named Odovacar, later to become the first Germanic king of Italy. This base was finally ousted in the year 471 by a Gallo-Roman force assisted by a British king referred to by the title Riotamos (“high king”), probably the central figure around which the composite charac-ter of the Arthur we know of today was founded.

Two major Saxon raids on Ireland occurred during the 5th century and the culprits could only have been the Loire-based pirates. Halfway between their base and Ireland lies Lands End, a more than convenient point for them to stop off and replenish water and food – almost certainly obtained by force. A leader such as Odovacar was more than capable of taking advantage of these unopposed visits and turning them into a major raid, or an invasion.

With Tintagel now acknowledged as an occasional royal seat of the Dumnonian kings, Arthur could well have been there, perhaps as a guest although Welsh traditions give him a Cornish home, a fort called Kelliwic. The two best candidates for Kelliwic, Castle Canyke and Kelly Rounds (Castle Killibury), along with Tintagel itself, lie within the region then called Pagus Tricurius, “land of three war-hosts”, now Trigg. If the legend contains a typically Celtic three-fold exaggeration, it is possible that the army led by Arthur consisted of these three war-hosts, along with their commanders, portrayed as “kings”.

Some have interpreted the Vellandruchar story as origi-nating with a 10th century campaign of the Saxon King Aethelstane against the Danes. There is an obscure tradition of him fighting the Cornish at Boleigh, above Lamorna and going on to conquer the Isles of Scilly but, in fact, there is no record-

ed evidence of him venturing any further west than Exeter, and his only campaign against Danes was in Northumbria, against a land-based faction. As for the Danes themselves, they are first heard of in Cornish history in 838 when they unsuccess-fully joined with the Cornish against the Saxon King Ecgberht at Hingston Down, and are not heard of again until 981, when they sacked the monastery of St. Petroc at Padstow, long after Aethelstane’s death.

The Vellandruchar legend, then, is far more historically feasible in an Arthurian context than in any other and, like so many legends, may well have its origins firmly rooted in reality.