This follow up article was also written in the 1990s by the great Cornish writer and scholar Craig Weatherhill who sadly died in 2020. Any article or book written by Craig would have been very well researched and his opinions based on his findings, not made up.

In a previous article “Where The Phoenicians Weren’t” I attempted to lay the myth of Phoenicians sailing to Cornwall for tin once and for all but, if the Phoenicians weren’t t carrying our the export trade in Cornish tin, who was!

We can only go on ancient records. going back to an amazing man called Pytheas. a 4th or 3rd century BC Greek living in what was then the Greek colony port of Massalia, now the French Mediterranean port of Marseilles.

Pytheas deserves far better credit than he gets as one of the greatest of all early explorers even though his original account of his voyage no longer exists and we have to go by quotes from him by later (though still early) historians. He was a talented geophysicist. who had used the stars to fix the latitude of his native town and even dirscovered that Polaris – the Pole Star – was not quite at the celestial pole. He even went so far as to accurately gauge the lengths of daylight on the summer solstice in various northern latitudes, implying that he not only knew that the earth was round, as had Aristotle, but had also calculated its diameter. Tin from Cornwall was customarily brought into Massalia for mediterranean merchants and Pytheas resolved to journey to is source. commissioning a Massaliote merchant ship for the job. One historian has pointed at that such a ship would have been 50 metres or more in length and up to 500 tonnes in weight, larger and better suited for ocean voyages than Columbus’ Santa Maria 1,800 years later.

Her crew is likely to have included a number of Celtic speakers (Massalia being in Celtic Gaul), which would have been vital for the voyage.

He hugged the coast, passing Gibraltar and turning north along the Iberian coast. He sailed around Biscay. noting that the land distance from Massalia to Biscay was far shorter than the journey by sea, and eventually reached Brittany (then Armorica). Perhaps he took pilots aboard, because he knew enough to abandon his hugging of the coast and to strike out across the Channel. He visited West Cornwall. circumavigated Britain, entered the Baltic and may even have travelled as far north as the Arctic Circle. The shape of Britain he likened to a triangle, the three points being Belerion (Land’s End), Kantion (Kent) and Orkas (the Orkneys), and its perimeter to measure 3,875 miles, so close to the actual figure as to not make much difference. What he saw we can only glean from other writers who quoted him, but it would certainly seem that he was the first Mediterranean seafarer to set foot on British soil. Diodorus of Sicily, writing in the 1st century BC., gives a wonderful description of tinning in West Cornwall which can only have come from Pytheas’ account:

The inhabitants of Britain who dwell about the promontory known as Belerion (a native Celtic name, meaning something like “The Shining One” and not Roman or Greek) are especially hospitable to strangers and have adopted a civilised manner of life because of their contact with merchants of other peoples. They it is who work in the tin, treating the bed which bears it in an ingenious manner. This bed, being like rock, contains earthly seams and in them the workers quarry the ore which they then melt down and cleanse of its impurities. Then they work the tin into pieces like astragali and convey it to an island which lies off Britain and is called Iktis; for at the ebb-tide the space between the island and the mainland becomes dry and they can take the tin in large quantities over to the island on their wagons (and a peculiar thing happens in the case of the neighbouring islands which lie between Europe and Britain for, at flood-tide, the passages between them and the mainland run full and they have the appearance of islands but, at the ebb-tide, the sea recedes and leaves dry a large space and, at that time, they look like peninsulas) [a perfect descrip-tion of Scilly at that time].

On the island of Iktis the merchants purchase the tin of the natives and carry it from there across the Straits of Galatia or Gaul and finally making their way on foot through Gaul for some thirty days, they bring their wares on horseback to the mouth of the river Rhone.

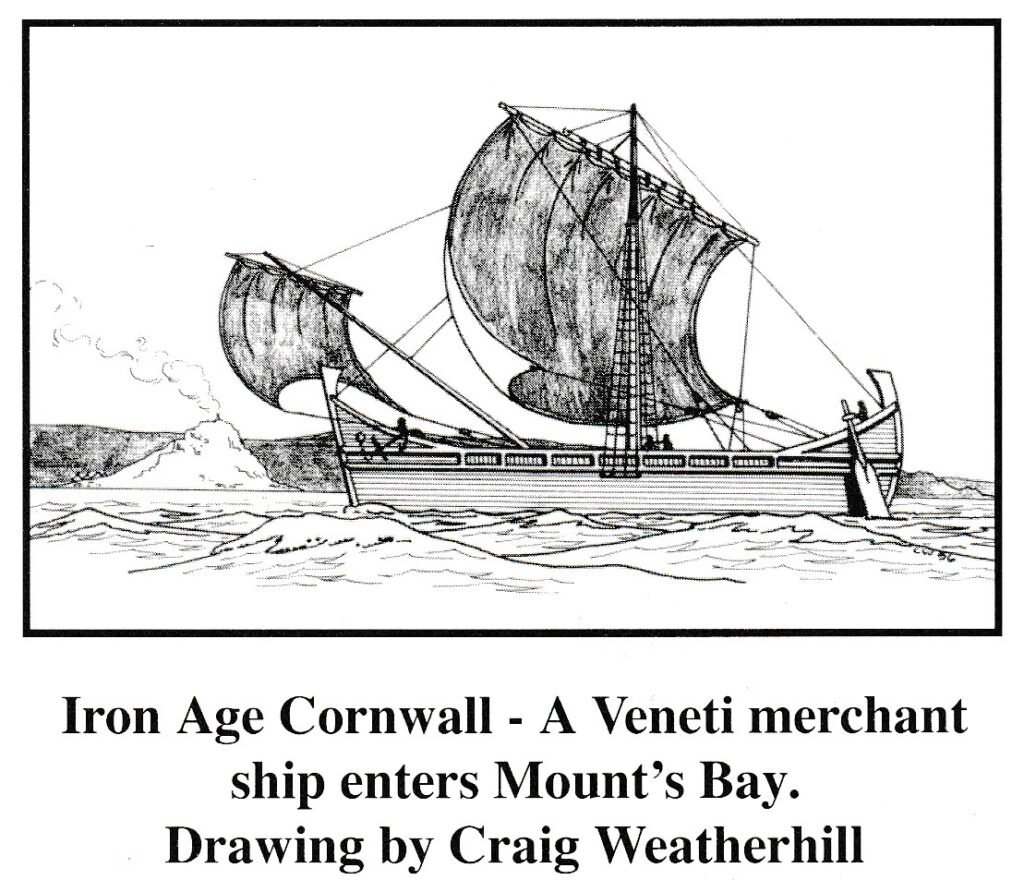

All sorts of theories have been put forward for the location of Iktis, even Kent and the Isle of Wight. The discovery of an Iron Age port at Mount Batten, Plymouth led some to declare the place Iktis, except that it doesn’t match the description in any way. In fact, several Channel ports existed in the Iron Age, only one of which is Iktis. This was obviously very close to the Belerion tin fields and description fits St. Michael’s Mount perfectly (and tidal conditions then were the same as now; the Mount’s Bay Forest was drowned 2,000 years earlier). The name Iktis implies an early Celtic ek-tiros, “off the land”. In the region of Vannes, southern Brittany, at this time was a powerful Celtic tribe named the Veneti, owners of massive ocean-going ships of oak which, as Julius Ceasar was later to record, dwarfed his galleys. These were solid and advanced, being equipped with anchor chains rather than ropes as Roman ships had, with high foredecks and sterns, but were sail-powered rather than oar-driven. Ceasar, seeking to break the stranglehold of Venetic trade in the Western Approaches, attacked and sank a fleet of over 200 of these merchantmen in the bay of Quiberon, during which he recorded an intriguing account of how the Veneti used their cliff-castles (very similar to the Cornish ones). The Venetic defenders shut themselves behind the defences until the Romans, having suffered much loss of sweat, blood and lives, were on the point of breaking in. Then the Veneti would whistle up one of their ships to come in under the cliffs, scramble aboard and sail off to the next cliff castle, where the Romans would begin the siege all over again (while, no doubt, some of the locals would nip back and repair the first one for use again). Ceasar also includes an intriguing sentence which implies that the Veneti fleet was reinforced by similar ships from over the Channel, in other words, that the Celts of South-West Britain had them as well. Studies have estimated that a typical Veneti ship was up to 35 metres in length and might have looked much as the illustration shows.

All rather different to the popular belief that the only boats the Celts had were coracles which, of course, river and inshore fishermen did use.

These were the ships that conveyed tin across the Channel to southern Brittany or even to the mouth of the Garonne, where it was taken on horseback through the Carcassone Gap to the “mouth of the Rhone”, in other words, Massalia, home of Pytheas. So, no Phoenicians, only a set of very enterprising Celts who, even though they eventually succumbed to the power of Julius Ceasar, still managed to keep the secret of the Cornish tin fields. Ceasar himself continued to believe that the tin came from somewhere in the interior of Britain, never twigging its real source. But here’s an intriguing question – as the Celtic ships were so large and solidly built, might they not have been easily capable of sailing the Atlantic? And, as a result, might such mythical Celtic voyages as that of Maelduin have been not so mythical after all, with the islands he passed being perhaps the Azores or even the Bahamas or West Indies? Now there’s a thought….