When the Australian “gold rush” commenced in 1851, many Cornish “Cousin Jacks” left their occupations in the foreign mining fields of America and Mexico to join other Cornishmen in their endeavours to make a fortune. We have grown up with stories of those who returned from such ventures with enough money to build a row of houses, or to buy a small-holding. Such a successful pair were John Deason and Richard Oates; the full story of whose remarkable fortune is only to be found, like others in this article, by the methodical research of Cornish newspapers of the period.

Australia 1869…. The sun blazed relentlessly from a clear blue sky. John Deason cursed the intolerable heat of the Australian climate and paused to wipe away the sweat which oozed freely from his brow. His partner, Richard Oates voiced agreement, expressing at the same time a longing for the cool breezes of a Cornish cliff.

Oates had emigrated to Australia in the early 1860s in search of work, leaving his family in a small cottage in the Land’s End peninsula. He had quickly found a good reliable partner in fellow Cornishman John Deason who had settled with his wife and family in 80 acres of land at Moliagul.

Unfortunately, Australia was proving to be not quite the Eldorado they had been led to believe. After several years of digging in search of gold they had met with no success. Their skill in following a lode underground through the hard rock was here completely irrelevant as they watched clerks, cooks and Chinese coolies become rich overnight with a “lucky strike” amongst the maze of shallow surface diggings. With no source of income times were hard, to such an extent that they had been refused credit for a bag of flour only a few days previously. Their claim was situated near Black Reed, Bulldog Gully, Moliagul, a short distance below the Wayman’s Reef about two miles from the celebrated Gypsy diggings.

Each day they had doggedly faced the burning sun to dig, sift and pan the parched soil, constantly would find a nugget that would at least enable them to buy sufficient provisions to survive in this distant land.

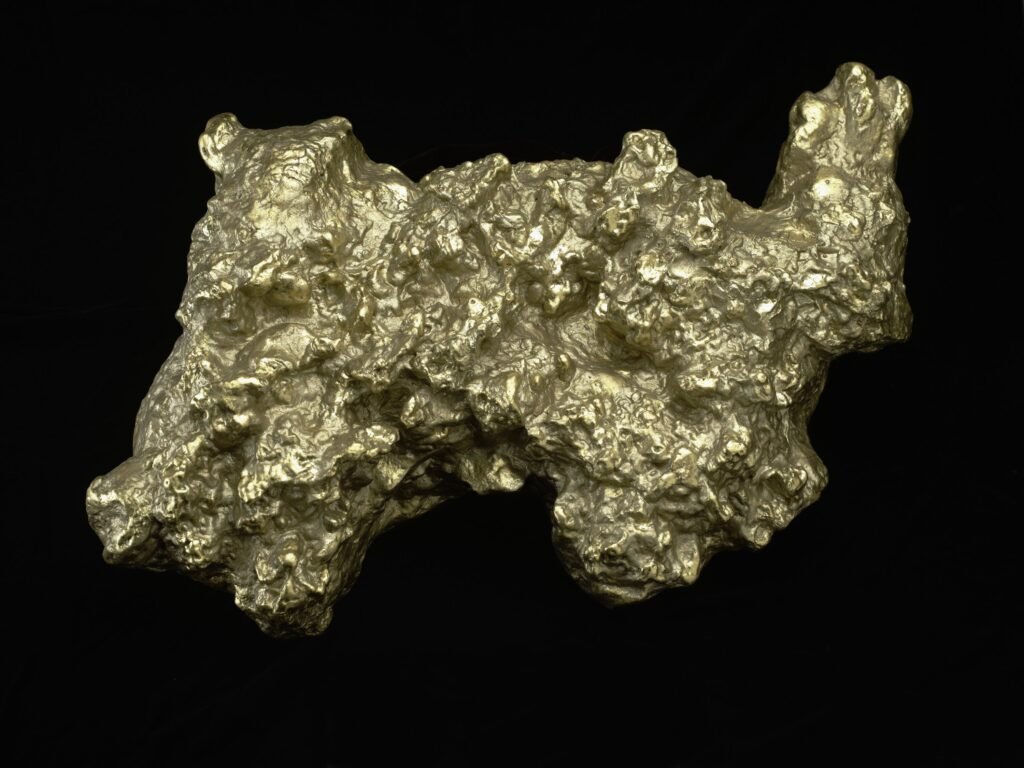

Deason now turned once again to the monotonous task of breaking the soil around the roots of a small tree. His pick had only penetrated the surface for a depth of two inches when he struck something hard. “Damn it!” he exclaimed, “Another rock! I wish it was a nugget and I’d broken my pick on it.” Stooping, he commenced to clear away the soil to determine the size of the boulder which appeared to be immovable at his feet. It was then that he realised the object might possibly be gold! With a whoop of delight which brought his partner running, he frantically scraped away the remaining top soil to reveal the nature and full extent of his find. With eyes wide open with amazement and disbelief the two Cornishmen gazed down upon the largest nugget of gold ever found! When it was eventually dug from the ground they heaved it into their small dray and headed for Dunolly, a small town nearby where they struggled with their welcome stranger into the London Charter Bank, depositing it at the feet of the astounded bank manager.

News of the great nugget quickly spread through the town, bringing all and sundry rushing through the dusty streets to the bank, where they pushed and clamoured to catch a glimpse of the find. A panting town constable arrived to control the crowd and to guard the prize whilst it was weighed – a staggering 210 lbs. troy. The stronger miners amongst them stepped forward at a challenge to lift the huge nugget and many exclamations of surprise were expressed at its immense weight and compactness. A sledgehammer and cold chisels were sent for and used to break the huge lump into several fragments, in readiness for smelting. It proved to be so solid that several of the chisels were broken in the attempt but, as chip after chip was removed, “it appeared as clean as well-cut Cheshire cheese”. After five hours of hammering, the monster nugget was pounded up and later smelted, the final weight being 2268 ounces. 10 dwts. 14 grs. of solid gold, (dwt is a penny weight – 24 grains) exclusive of at least a pound weight, which was given by the ecstatic finders to their numerous friends. The bank manager immediately acquired the gold for £9,600 a sum which today would be magnified many times over. The “Cousin Jacks” had made good at last; the “Welcome Stranger” nugget had been appropriately named.

We do not know how this eventually affected the lives of Deason and Oates but it was reported that a few days afterwards they were working away at their claim as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened. Richard Oates was then planning to visit his family at Land’s End, with some regrets that the nugget had not been photographed or drawn before it was broken up, for it would have made it more believable when he told his incredible story in the public houses and cottages of his native West Cornwall. Although not as pure as that found by the two Cornishmen, the largest nugget of gold ever mined was a huge lump of black slate and gold which weighed 630 1bs., and when smelted was worth £12,000. It was found by two partners, Holtermann and Beyer, in 1872, at Hill End in New South Wales. When gold was discovered in the Transvaal, South Africa, in 1873, amongst the first to make the long journey from Cornwall were two brothers from Wendron, George and John Thomas. Both were experienced miners who had at one time been the landlords of the Miners Arms at Wendron. Their claim on the De Kaap Goldfields proved to be immensely rich. Working beneath a relentless sun, they had sunk a shaft into the hard rock and found rich gold deposits, described as “gold with a little quartz to hold it together”. “Thomas’ Shaft” and “Thomas’ Reef’ became famous, as the brothers banked £25.000 after the first sixty-feet had been sunk. Whilst one dug out the rich quartz, the other crushed it using a small battery of three stamps, and the assistance of donkeys. Once crushed, the gold was separated by water, using techniques learned on the mines and tin-streams of Cornwall. Numerous offers were made for their rich mine which they finally sold to a company which started with 100,000 shares at £1.00 per share. These soon soId, and the brothers, who had bought 10,000 shares each, found their value doubled. The wealthy pair returned with their fortune to Cornwall in 1887, and in that October John, no doubt lebrating his success, was fined for being found drunk at Helston! Later that year he is reported to have bought Trenethick, in Wendron, with its impressive Tudor dwelling, for £11,500, a property which he must have seen when a child, but had never amt that he would one day own. Not only miners made huge fortunes. William Chapman of St. Teath emigrated to America to become a giant in the American slate industry. His in 1903, at the age of 86 years, was reported in West Briton and revealed his extraordinary life story.

His father, William, was a slater employed in the Delabole Quarries, owned by Lord Thomas Avery. During the French Wars, Lord Avery financed a company of ninety militia for the British army, making William a Lieutenant. Some of the wives appear to have travelled with them to the continent, as when William was severely wounded at the battle of Waterloo, his wife, Elizabeth, was present to nurse him back to health. Whilst in a village to the south of Brussels, she gave birth to William, the subject of this story. In Cornwall young William worked, from the age of seven, alongside his father in the slate quarries, developing into an expert in the trade. He then moved to the newly opened Devon quarries before achieving a post as superintendent of the quarries of Sir John Francis in Wales.

Encouraged by Sir John he emigrated to America, in 1842, to prospect for slate deposits. His quest was successful, and by 1850 he owned the extensive “Chapman Slate Quarries” which he leased, and later purchased. His endeavours made this the largest slate business in America, worth $400, 000 dollars in 1864. His materials were used to roof all the major buildings of the expanding city of New York before skyscrapers evolved. With “The Chapman Borough” named in his honour, he stamped his name in that great country’s history. No doubt there were many other successful emigrant Cornishmen whose stories failed to appear in the local press, but for everyone who was successful, a hundred were buried penniless, in some foreign soil.