All general photos taken at Geevor in 2020 by Terry Harry

The area in which Geevor Tin Mine operated was first worked by the old miners in the Wethered section of the mine. It is not known precisely when mining began, but in the old workings in the Wheal Carne area there is a date 1791 cut into the wall of the adit (drainage) level. During the period of the Boer War some Cornish miners from South Africa came home and took up a lease on the property to prospect the mine, with satisfactory results. Geevor Tin Mines Limited was formed in 1911, and took over the property.

The mine was then served mainly by the Wethered shaft (named after the then chairman of the company) on which sinking started in 1909. For the next few years, mining and development was concentrated around this shaft although ore was obtained from the neighbouring Wheal Came shaft and workings to the east. However, as lodes were developed to the west of Wethered shaft it became apparent that the future of the mine lay in this direction. Accordingly, the sinking of the Victory shaft was commenced in 1920 at a point approximately 1660ft. to the west of Wethered. Wethered shaft remained in use until 1944 when hoisting there was discontinued and the aerial ropeway, used for transporting ore from this shaft to the mill at Victory, was taken down. Ore obtained from the mine occurs in a number of steeply inclined lodes which vary in width from 4 inches up to approximately 6 feet, a representative width of those worked would be 15 to 20 inches. The lodes at Geevor lie almost entirely in the granite country rock. In the old Levant Mine, which lies south west of Geevor, the lodes are mainly in the “killas” country rock and the Levant North Lode is a continuation of the Geevor No. 2 Branch Lode, at greater depth. By the 1960s, the series of lodes worked in the Victory section of the mine had been fully developed, and that in order to continue production at the same rate, the old mines adjoining the property would have to be investigated. It was discovered that a breach from the sea bottom into the upper levels of the old Levant Mine had occurred since its closure in 1930. It was therefore obvious that the re-opening of the mine would pose considerable difficulties.

In these circumstances, in order to obtain a quicker return from the development, tunnelling towards Boscaswell Downs Mine was started, and Simms Lode -named after a former chairman and managing director -was found some 2,000 feet from the main series of workings. This section of the mine was developed and exploited during the period in which the hole through the sea bed into the Levant Mine was being plugged and the workings dewatered. This project at Levant Mine being undertaken jointly with Union Corporation (U.K.) Ltd.. All ore and the majority of men and materials, were handled through Victory shaft. This is a vertical, three compartment shaft, 15ft. by 6 ft. within the timbers, which are hung and blocked at 7 ft. centres. Two of the compartments are used for hoisting, while the remaining one contains a ladder-way, pipes and cables. Initially sunk to the 5th level, the shaft has been deepened as it became necessary to follow lodes in depth. Level stations are at nominal 100ft. vertical intervals, starting at the 3rd or adit level. A new 110ft. high steel headframe was supplied by Mechans Ltd., Glasgow, and erected at this shaft in connection with the modernization programme after the Second World War. This steel structure replaced the original timber headframe that had served the Victory Shaft since it was sunk. Incidentally, it was named Victory Shaft after the hostilities of the First World War.

A new 450 h.p. double drum electric winder with 10ft. diameter drums was commissioned in autumn 1954, superseding the steam hoist previously employed. To assist in the mining of the area, to the north east an old shaft of the Boscaswell Downs mine, Treweeks Shaft was rehabilitated in the mid 1960s. It was furnished with steel buntons and runners (guides) for the cage. As the old shaft had been sunk on lode, it had to be realigned. This shaft had two compartments, one for hoisting men and materials, the other for a ladderway and pipes and cables. Since then the mine continued to expand, with a major extension to the mill in 1979, when the new table plant was constructed. In the early 1980s, the old Wemco drum separator was replaced with a Tri-Flow separator. This piece of equipment increased the capacity of the plant by enabling a mineral / non-mineral split to be made at a rate of 45 tonnes per hour. This expansion programme also included the development of the sub incline from the bottom of Victory Shaft, downwards and outwards under the sea to access the downward trending lodes. This was opened by the Queen on 28th November, 1980.

Surviving The Tin Crisis.

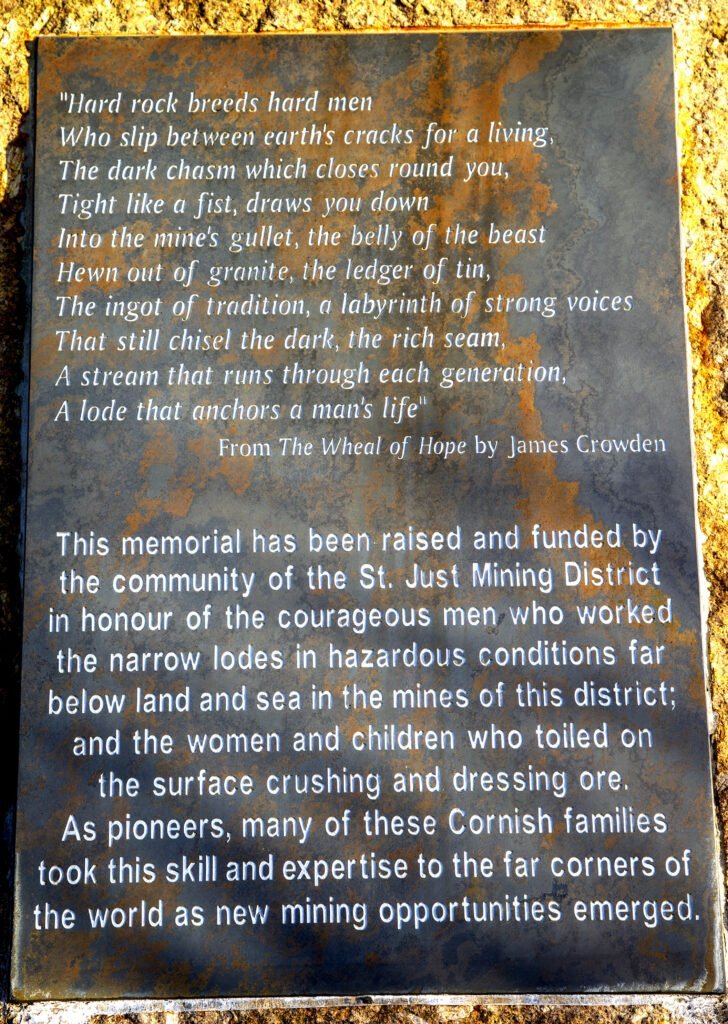

In October, 1985, the sudden fall in the world tin price created the Tin Crisis. The price paid for metallic tin plummeted overnight from over f10,000 per tonne, to £3,400. Without help, no Cornish tin producer could survive the crisis. In the eventuality, the following operations went out of business, Wheal Concord, Wheal Pendarves, Mount Wellington, Hydraulic Tin, Brea Tin, Cornish Tin & Engineering, and by 1992, Wheal Jane was also closed – all with the loss of many jobs. At the time, Geevor, together with the owners of the South Crofty-Wheal Jane group, looked to the Department of Trade and Industry for cash help. After a protracted period, during which hope at Geevor gradually gave way to despair, South Crofty and Wheal Jane were offered a £25 million package, and Geevor nothing. In April, 1986, in a blaze of publicity, protest and emotion, Geevor Tin Mine closed. It seemed that over two thousand years of mining at St. Just had ended.

A few months later, the new managing director, Mr. Nasser, recruited trammers to remove the broken ore, which was still standing in the stopes. This was to be the last operation before the pumps were to be switched off, and the mine allowed to flood. Many saw this as the “last rites”. The trammers removed 44,000 tons of ore before that phase ended. However, it was not the end. When Eric Grayson became chairman in October 1987, he was approached by a former shiftboss, Kevin Williams and others, with a rescue package. The following month preparations began for re-opening the mine for full production. Clearly, for the moment, development was out of the question, with the price of tin still below £4,000, but it was estimated that stoping, pillar recovery and tramming could continue for up to seven years with a low tin price.

On 4th January, 1988, Geevor went back into production with less than 100 miners and a weekly aim of 2,000 Tonnes of ore hoisted… it was never going to be easy. The price picked up and miners returned from Australia, the Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Canada, South Africa and several parts of this country. Production was slowly increased until by late autumn, the mine was making a profit. Subsequently, the price of tin fluctuated rapidly, rising to £6,000 per Tonne and dropping disastrously to well below £3,000. On 16th February, 1990, the miners were laid off, and Geevor went onto a care and maintenance programme with only a skeleton staff. During the next year the mine continued to take visitors underground, with the tourist side of operations having a turnover of £104,000 – despite the lack of funds for any advertising. At the same time, some of the underground conveyors and a winder were removed. The pumps were switched off in May 1991, but the underground tours continued until 6th September, 1991, when the operation was wound up and the skeleton staff laid off. More months of agony and indecision followed as the surface plant that represented so much to those who felt deeply about the old mine, was smashed to pieces by scrap men. Valuable machines were destroyed, buildings were neglected to the point of ruin and the whole area assumed an air of doom and depression. Gradually out of this scene of despair emerged signs of hope. the Cornwall County Council purchased the site and the Trevithick Society, the National Trust, Penwith District Council were moved by the many individuals who felt that Geevor should not be allowed to merely disappear. One of these individuals, Bob Orchard, the ex-chief engineer of the mine(the author of this article), was certain that the mine could be developed into a Mining Heritage Centre, which would eventually create jobs in a very depressed area. By August, 1993, a museum and visitor centre had been sufficiently developed to allow local people and visitors alike to appreciate the fascinating story of St. Just mining as so recent1y represented at Geevor Tin Mine. The work of adapting the old mine offices and moving and creating a museum was down to Bob Orchard and group of volunteers – ex-Geevor employees – who worked through the winter with no heating or mains power but with a dogged determination to make it happen. which culminated in the official opening on 2nd August, 1993. Bob Orchard takes up his own story, “Since then, to date it has still been a bumpy ride. There have been moments when I have felt as though I am trying to push water up hill with a hat pin and other moments of great satisfaction when pet projects came together. One of the greatest problems we have to contend with is that of vandals and burglars, as it consumes vast amounts of time and resources in just putting right the mindless damage, when there are many other positive things which also need our attention. “I think it would be fair to say that from a commercial point of view, we have proved that there is a potential to develop the site as a Mining Heritage Centre. Not only dealing with Geevor, but with hard rock mining in general, for it is the Cornish who took their mining skills all around the world. Here at Geevor we have the unique site, with most of its plant and equipment still in situ, together with examples of underground equipment which have been brought to surface. “Here on one site there is the opportunity for the interpretation of all aspects of mining, mineral processing and mining, machinery, and if the development ideas I have for the site can be made a reality there will be lots of “hands on” experiences for those who visit the site. “This season we have introduced tours – which have proved very popular even though we do not take visitors underground here at Geevor but at the Rosevale Mine. The tour caters for adults, children and educational groups, who are all kited up with wellies, hard hat, dust coat and miners’ cap lamp, then bussed to the mine – which involves a short walk up a picturesque valley to the mine portal – and then the mine tour which involves in excess of an hour tramping along levels and crosscuts, climbing laddenvays through stopes, water dripping down the back of the neck, hand drilling demonstrations… by candlelight. Generally enjoying being in a time warp, back to the turn of the century, in a genuine tin mine which has taken over twenty years to restore to its present state, suitable to take the public into, give the proper feel of a mine and comply with modern health and safety regulations. From this season’s experience, it is recommended that anyone wishing to go on an underground tour should pre-book, as each tour is limited to groups of 16. “Having said all this about the tour to the Rosevale Mine, it is still hoped to develop an underground tour here at Geevor, down to our third level (adit level). This will enable visitors to go down in the cage, just like the miners. At this stage a feasibility study has been undertaken, and from the technical point of view is possible… but it is going to cost a considerable sum to implement it. But, having said this, the Durham County Council have, I believe, just spent three quarters of a million pounds creating an artificial underground lead mine for the public to visit at Killhope lead mine…. We have the real thing beneath our feet, here at Geevor, in solid granite.