There are two occasions when you can guarantee that the Cornish will gather in great numbers – at a concert by a good male voice choir, or when Cornwall appears in a county cham-pionship rugby match.

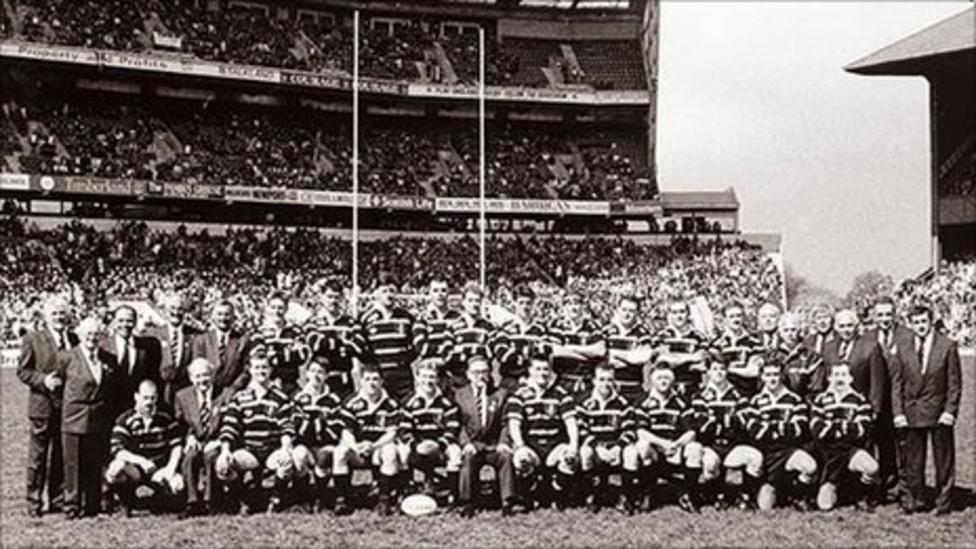

Although with the constant migration of our better players to the more prominent of the English clubs led to a decline in the standard of Cornish club rugby, the unforgettable win over Yorkshire in 1991 at Twickenham illustrated that the great enthusiasm for the game still remained with the Cornish people.

It had all started in the 1870s. Here, in a mining area, the background was similar to that in Wales and Durham where it was played chiefly by the working class, following its intro-duction by the more affluent returning to Cornwall from the public schools and universities of England. The Cornish had for centuries enjoyed the tough, physical, contact sports of wrestling and hurling, and with their decline, “football”, as we still call it, was eagerly seized upon as a substitute.

At Redruth we were raised with tales and legends of such rugby immortals as Bert Solomon, “Maffei’ Davey, Roy Jennings, Faviell, and “White-top” Curnow, some of the countless number of highly talented players who represented Redruth, Cornwall or England. One can still recall seeing, each Saturday afternoon in the fifties, the becapped figure of Bert Solomon standing behind a windbreak of privet, outside of the ground, overlooking the “Camborne” end of the pitch. From there he watched in solitary silence, probably dreaming of his own golden past in the early years of the century when he mesmerised opposing players with that devastating dummy which enabled him to score against Wales, in the first ever international at Twickenham, in 1910.

A reserved, unassuming man, Bert chose not to enter the ground and clubroom at Redruth where he could have basked in his legendary past with an ever full glass of free beer; outside he was safe from the adulation which would have been bestowed upon him. His eldest son, Stoyle, with whom this writer played rugby at that time, recalled, that as a youth, following a walk with his father to Cam Brea, they stopped at the Buller’s Arms, in Falmouth Road, for a drink. They had only then had it placed in front of them when another man entered and engaged in conversation with the landlord. The latter must have told the man that the legendary Bert Solomon was stand-ing near him because he promptly came across, hand extend-ed, voicing praise about Bert’s prowess. The adulation was all too much for Bert – he dropped his glass and quickly left the pub. Such was his modesty. Both of his sons told this writer that following his first and only appearance for England, he disliked the publicity and adoration so much that he declined his selection for England on subsequent occasions.

This was in the 1950s when Cornwall was still largely unaffected by the way of life, and so called “progress” of those across the Tamar: life had remained little changed from pre-war days. Rugby players had returned from war service eager to resume the traditional way of life and their rugby careers. From Truro to Penzance it really was a way of life. We, as young men, ate. drank. and slept rugby, spending the whole week like hounds on the leash awaiting to play on the Saturday. With no other sporting facilities available, no sophisticated leisure centres. no television. and with only motor bikes for transport. leisure time was spent mostly within our immediate area – and nearly all young sportsmen played rugby. This keen-ness created great competition for any position in both senior the latter then stronger than some senior and junior teams. sides of today.

When Redruth held its pre-season trial matches, there were often sixty players of good calibre on the bench, and thirty on the field, all being given a chance to prove themselves. For the majority. it was the culmination of several seasons playing in the hard school of junior and reserve teams. The trials were renowned for their physical aspect as each player vied with his opposite number to outshine him – it really was an arena of survival.

Unlike today there was no intensive coaching; players learned the rudiments by playing alongside older, more experienced players, who had often played both senior and county “football”. Natural flair was therefore allowed to flourish, and abounded in three-quarter play. One recalls the three-quarters of the St. Ives club particularly: all appeared to be blessed with the inborn talent of side-step. jink. dummy. change of pace, etc.. Players such as the late Harry Oliver. a magnificent play-er who, with a slight feint of the ball. a wiggle of the hips, was past you like a shadow! Harold Stevens. probably the best all-round player in Cornwall since the war, was also a St. Ives man, but played most of his rugby for Redruth. The forwards of today are bigger and fitter, by today’s standards, but the three-quarters lack that natural flair, and even if possessing it often have it “coached out of them-, as is the common com-plaint of today.

Such talent made Cornish teams equal to any in Britain. One recalls the annual visit of John Williams’ XV to Redruth, always a virtual Lions side, and of the two devastating tackles made by Freddie Bray, the Redruth full-back on Geoff Butterfield, the England centre.

This writer (Michael Tangye) was one of those at that period who played junior rugby for Redruth Albany, then recognised as the best of Cornish junior rugby clubs. and regularly ending the victorious runs of the numerous talented reserve sides: it is now of interest to reflect on the experiences of those now distant days. We travelled to away fixtures by coach. at a time when cars were a real luxury. The singing. and “card-school”, enroute built up a good team spirit, further strengthened by all remain-ing after matches. Any journey across the Tamar into Devon meant using the Torpoint Ferry, as the bridge had not then been constructed. The last ferry left at midnight and if playing in Plymouth the bus met us there at that time – if it was missed one was left stranded there all night. At the appointed hour, taxis arrived to discharge players assisting “legless” colleagues, whilst the more sober, whilst waiting, have been known to swim across in darkness for a bet, collecting their clothes and joining the bus on the other side.

Short tours to Nottingham and Northampton were common, and with no motorways and few, if any, dual carriageways, the journey took many hours – arriving at dawn and playing a few hours later! One match was usually against the Northamptonshire Police, always a team of giants. The inn where we stayed on one occasion was frequented by a number of Irishmen who hardly enjoyed a good relationship with the local constabulary. When word spread that we were matched against the latter, a crowd of the Irish insisted on supporting us. Although physically dwarfed Albany tore into the opposition with the then traditional Cornish physical game, and outplayed their larger opponents – to the great delight of the Irish who, clutching their beer bottles, ran frantically up and down the touch-line, jumping into the air! That night, following the victory, the Irish treated us like heroes, buying all drinks, and excitedly recounting to everyone of how, “The boys beat the Pol-iss!”

One recalls the acoustics in the Northampton City Police H.Q. which was irresistible for a session of harmonising, as singing was then a great feature of Cornish rugby teams. With the tradition of Methodism still strong, hymns featured promi-nently, along with bawdy songs. On one occasion our police hosts took us on a tour of the night spots of the city. One was frequented by rather high-class prostitutes who sat on high stools at the bar, revealing ample areas of leg and thigh. One can never forget their amazed expressions as the team gave a rendering of The Old Rugged Cross !

Local village rugby sides were of a high standard, and produced fanatical partisan support to the extreme. To play against St. Day was an awesome experience, as not only were the players hard, but the spectators were harder. A wing, with his back to the baying crowd when throwing the ball in at a line-out, was commonly belaboured with the walking-sticks of old men and by sly punches and kicks from small boys, whilst all around, women of all ages screamed abuse! Any team unfortunate to win, ran from the field as quickly as possible before missiles rained upon them. On one occasion windows in the bus of the Redruth reserves team were smashed by stones as it was frantically driven from the village.

Troon was also a close-knit community still retaining the old Cornish Celtic tribal tradition – to regard anyone from beyond the precincts of their village as a natural enemy. Their players, hard and talented, would “rather fight than eat meat” and their use of the boot was such that it was said “they would kick the eye out of a needle”, or “anything above grass”!

Stithians was also a formidable side who regularly fielded a team who were nearly all related, with the Burley family pre-dominating, with fathers playing alongside sons. Their nickname, “Tigers”, could well have originated form the large number of scratches from uncut finger-nails which festooned the bodies of the opposition following a match – the scissors had probably not then reached the village!

Unlike today, changing facilities were then quite primitive, or non-existent, as at Carharrack, where players changed on the field in the depth of winter, leaving clothing up in the hedge. At St. Day, and elsewhere, the local pub provided an outbuilding with a loft and two tin baths of hot water for washing after a muddy game – “One for hands and faces, one for body”. Inevitably two of the largest forwards would flop in each and, as one player said, “You’d get just as clayne (clean) rollin in a ploughed field!”

One doubts if the players of today would be keen enough to endure such conditions for fun, but we accepted it all without question, and if a Saturday fixture was cancelled we would rush around seeking a game with any club who required a player. Some of us went on to, if only briefly, wear the then cov-eted red shirt of Redruth – rugby in Cornwall was truly an expe-rience, a way of life.

Sadly, no longer at Christmas do the “changing pavilions” ring with local carols, before and after a match – but as this writer witnessed, today they have been replaced by the thud of foreheads being banged monotonously against walls, and the chanting of “Kill! Kill! Kill!” as players, intent on winning at all costs, “psyche” themselves up for the ensuing conflict.