1960. I sat in the kitchen of the farmhouse at Pelistry, on St. Mary’s, and chatted to ninety- year-old Mrs. Tregear about the Scilly she knew as a child. It became immediately obvious that, like many of her generation, the traumatic experience of the wreck of the Schiller, in 1875, lingered vividly in her memory. “I remember seeing the body of a little German girl washed onto the beach – her beautiful long hair stretched out on the white sand, and her purse tied around her neck.”

With a death toll of 301, there had not been such loss of life on the rocks of Scilly since the Association and three other vessels of the British fleet were wrecked in 1707.

The wreck of the Schiller has been reasonably docu-mented, but the aftermath, which so directly affected the islanders, has largely been ignored; it is only by researching the various Cornish newspapers of that time is the full story disclosed, along with some quite alarming statements which were not made until after the inquest.

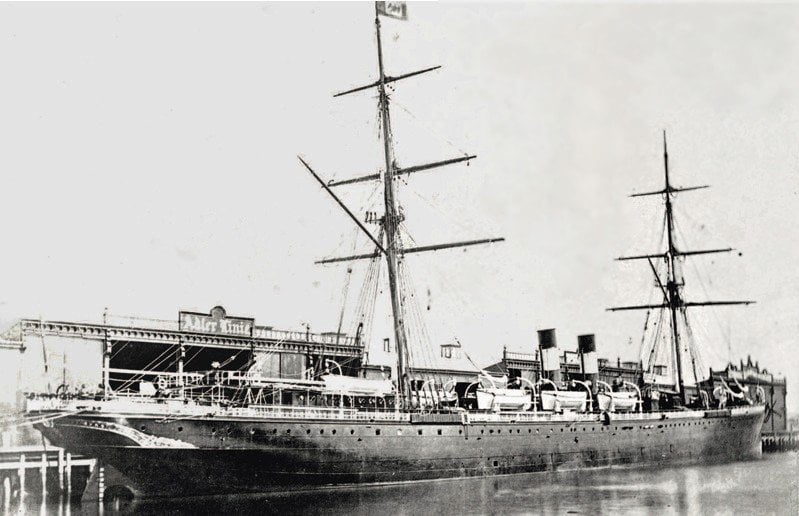

The Schiller was a large iron steamer of 3.421 tons gross. 380 feet long. 40 feet wide and 24 feet depth in the hold. There were two decks and a spar deck. She had 600 h.p. engines, two funnels, and two masts with sails. Owned by the German Transatlantic Steam Navigation company of Hamburgh, she left New York for Hamburgh, via Plymouth, on April 27th, 1875, with 254 passengers and 101 crew, nearly all German. Her general cargo included the Australian and New Zealand mail, and 300,000 20 dollar gold American coins worth £60,000.

She was captained by the experienced Captain Thomas, a neutralized German, who had risen from cabin-boy to Chief Officer in the Peninsular and Oriental Line, which he left in 1872 to command the Schiller which was built the following year.

The voyage was ill-fated from the start. The pilot at New York would not take them over the Sandy Hook Bar until noon on April 28th; their propellers then became fouled by fishing nets, which caused further delay. Finally, the crossing, leading up to the disastrous wreck, had been so bad that all the crockery and glass had been smashed, and for two days pas-sengers did not come up for meals.

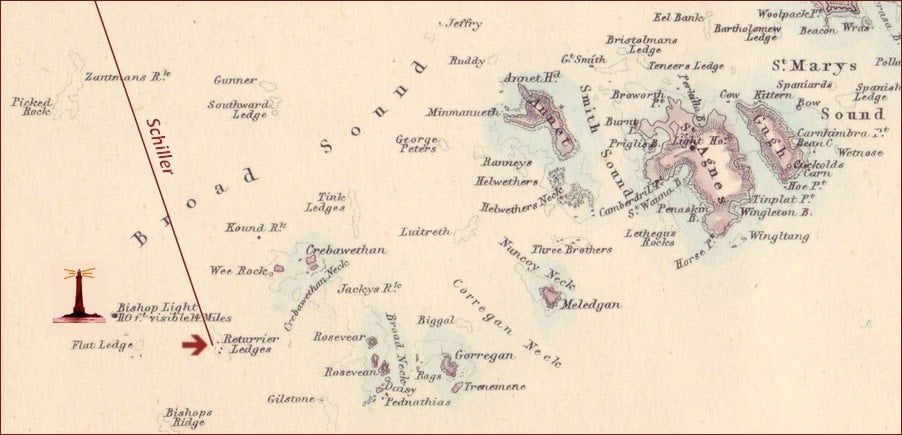

Despite the delays, Captain Thomas, renowned for his past voyages, was on time when he approached the Scillies in a dense fog and heavy sea. He was due to arrive at Plymouth the following day, Saturday May 8th. He had earlier held a consultation as to their position, but believed himself to be some Twenty miles west of the rocks of Scilly. However, a strong south westerly gale and strong drift currents had taken them off course to head directly for the Retarrier Ledges, near the Bishop Rock lighthouse.

Because of the dense fog the vessel proceeded at half speed, with her sails taken in. It was 10.00pm. on Friday 7th May; most of the passengers had retired to bed. Suddenly the Schiller struck the ledge, grounding several times before breaking her bottom. The sea rushed into her forward compartments and engine room, extinguishing the fires. There was instant panic. Women and children, awakened by the terrible shudder, ran from their cabins screaming. Then followed the alarm, the muttered prayers, curses, the noise. the scrambling, fighting, the wild stampede from stem to stern.

On deck. Captain Thomas organized the firing of signal guns and distress rockets whilst lifebelts were hurriedly distributed, but all were masked by the dense fog, and even the lighthouse keepers saw nor suspected nothing, thinking the guns signaled the passing of a vessel past the light.

There appears to have been little regard for the women and children as the crew and male passengers rushed to the eight lifeboats. Captain Thomas attempted to maintain order by firing his pistol over their heads, and when his cartridges failed, called for his sword to clear the overcrowded boats of the cowardly men. only to see them fill again. Of the eight crowded boats only one was successfully lowered to get clear. the others stuck in their davits and had to be cut loose. One was dashed against the funnel which toppled and crushed the occupants of another and four were swamped by waves which swept across the decks of the Schiller washing others to their doom.

Some took to the rigging. Thirty-five found temporary refuge in the iron foremast, where they were urged to climb higher by a Captain Percy, a passenger, whose brains were subsequently scattered by a heavy chain when he reached the crow’s nest. A Mr. West, also in the crow’s nest. used his body to shelter himself and was later picked up by Obadiah Hicks of St. Agnes. Others, who had lashed themselves to the latter, whilst heavy seas broke over them. were to be drowned when the mast crashed into the sea.

Between 1.00am. and 2.00am. the pavilion over the saloon in which the women and children huddled together clad in lifebelts, was suddenly washed away by a huge wave. Many male survivors would never forget the terrible screams as they were swept to their deaths. An hour later, Captain Thomas, who had vainly attempted to control his cowardly German crew and the male passengers, was himself swept overboard and drowned. The screams of the victims continued until 4.00am. that Saturday – and then there was silence. Pilots on St. Agnes had heard the gun reports, but not knowing where to go, did not set forth in a gig until 4.00am.; they were on the point of returning in the morning gloom and fog when they spotted the Schiller with some survivors still clinging to its remaining mast. They rescued seven men, including the First Officer before reaching St. Mary’s at 8.00am. to raise the alarm. Some summer fishing-boats, and the passenger vessel Lady of the Isles, towing the lifeboat, hurried to the scene, only to find the remaining mast had gone – too late to save any lives, but salvaged twenty-five mail bags and brought seven bodies back to St. Mary’s.

In the meantime, the only lifeboat to be lowered success-fully from the Schiller landed with its twenty-seven survivors at Gimble Porth, Tresco. Amongst them was the only woman out of over a hundred to survive, a Mrs. Jones.

Then came the aftermath as the people of Scilly and the world became aware of the terrible death toll – out of 355 people 312 had perished! The passengers had been mainly German; the survivors had to proceed to their destination. Those bodies which were found required identification and burial; that Sunday fifty were landed at St. Mary’s and placed in a store on Rat Island, adjoining the quay. There they were laid out by two old widows whose husbands had drowned thirty years before – “an old grey-headed man, a handsome young girl of 15 years, and a little boy…” etc. Thirty-three of the fortunate survivors, including Mrs. Jones, the only woman, were taken to Penzance by the Lady of the Isles, where hundreds congregated to see them land.

The burials commenced on the Monday at 4.00pm. A long line of two-wheeled carts, each led by their drivers, and each containing two black painted coffins surmounted by posies, processed from the quay through the silent, empty streets. Behind followed the mourning local population headed by Mr. Dorrien Smith. Herr Roedner, a first-class passenger, who had survived by clinging to wreckage. walked, broken-hearted behind the cart which bore his wife and 6-year-old son; young men, in the regalia of the Order of Templars, accompanied one cart bearing one of their Order.

At Old Town churchyard two graves had been dug, each 25 feet long, in which the coffins were laid to rest in two layers. Over the following days Scillonians and Cornish fishermen arrived constantly with bodies hidden beneath sails – “a stout lady, a male with arms stretched out from his side.” “A woman on Tean, another on Maiden Bower.” “A female eight miles south of Scilly; two pregnant ladies” – whilst upwards of 50 bodies were reported floating past by keepers of the Seven-Stones Lightship.

Yet another mass grave was blasted and dug at Old Town and the mourning processions continued. On Sunday May 16th, children attended a funeral service along with officers and stewards of the Schiller and Mr. John Banfield, the German Consul of Scilly. Two of the deceased were Mr. and Mrs. Auguste Munte, of New York, who were married on the day the Schiller sailed.

Reporters, who had come in great numbers, wrote of the great compassion shown by the Scillonians when dealing with this terrible aftermath. Jacob Woodcock of Old Town, on finding the body of a five-year-old girl in the waves, took it to his home instead of to the “Dead House”. His wife “tenderly washed the brine out of its drenched clothes and washed its face and combed its hair.” Rather than transport the child’s body in a cart, he wrapped it in a shawl and carried it to Hugh Town. Later, the body of her little brother was washed ashore, and again they repeated the services, before finally attending the internment. There was praise too for the honesty of poor Cornish fish-ermen who handed in numerous valuables which they could easily have kept. A Newlyn crew retrieved the body of a young woman “with rings bearing jewels and amethyst, a gold bracelet, a gold pencil case”. A Porthleven vessel, on finding a decomposed body. said the funeral rites before sinking it, and the crew handed in 43 gold pieces and 4 gold rings at Penzance. Some bodies were not retrieved by superstitious fishermen who believed it was bad luck to have a corpse on board.

Over the following weeks, in order to cope with the constant funerals, coffins were sent from Penzance. At Old Town each internment was marked with a piece of wood, painted white, with sex indicated on it, or “Child”, and a record was kept of distinguishing marks. In cases where the identity was known they were placed in stout shell coffins, lined with lead, placed in outer coffins, and enclosed in strong wooden cases. Many, before being transported to New York via Liverpool, were embalmed by a London embalmer, and Mr. George Olver of Penzance. Over the following weeks the disintemment of bodies presented a more saddening spectacle then the first series of this awful tragedy. Relatives made the long journey from Germany and America to identify loved ones. Messrs Duckfield and Evans, two friends, travelled from New York; the former had his wife and one daughter disinterred – one daughter was missing. Mr. Evans had his son’s body taken up – “He fell on his knees broken-hearted to kiss the child’s forehead, and both men broke down.”

Decomposed bodies continued to be washed up for many weeks after the wreck and burial services were held at Paul, Penzance, and in North Cornwall.

The general cargo was also washed up along the Cornish coast, and by August 1877, the last of the 20-dollar gold pieces was salvaged. Out of the total value of £60,000 most of it had been recovered, by which time the wreck was enshrouded with seaweed.

Many bodies were never recovered. Rewards were adver-tised for their finding. The grieving husband of young Louise Holzmeister described her clothing and jewellery and offered £50 for the delivery of her body.

Franz Hauser travelled from Iowa, U.S.A., seeking the bodies of his mother and two sisters. He employed two divers at Penzance and made several descents on the Schiller. Eventually, he found the body of one of his sisters, some distance from the wreck, held firmly in the clutches of a gigantic cuttlefish with tentacles over twelve feet long and not less than a foot in diameter. Three days later he died from the shock.

The two divers made sworn statements of the facts, and presentation was made to the British Admiralty for a scientific search of the Retarrier Ledges to ascertain whether these tremendous creatures fed on human victims of shipwrecks. It is known that such large cuttle-fish were found in the waters of Cornwall and Scilly at that period.

When the main and final inquest was held in late June the survivors were far distant, and unable to give evidence. The fact that Captain Thomas and his officers were unaware of their true position was revealed, and it was regretted that there was no casting of leads, the normal procedure, which would have possibly avoided grounding. However, other disturbing facts were to be published the following year. Mr. Henry Stern, a saloon passenger, who had earlier reported the sequence of unfortunate events which occurred to delay the start of the voyage, told more facts to a Canadian newspaper.

“The disgraceful truth is there had been a social spree upon that ill-fated ship that afternoon and evening which is suffi-cient to account for all the neglect, confusion, and loss of life of that dreadful hour. Mr. Stern of New York, a saved pas-senger, said, ‘Many of the crew and passengers were intoxicated, one of the officers having celebrated his birthday that evening.’ One of the Schiller’s officers informed a news-paper correspondent that many persons on board were drunk when she struck and that many firemen and steerage passen-gers lay helpless until they were swept away by the waves. A gentleman, lately in Paris, said the birthday celebration is spoken of there freely, as accounting for the accident.”

If this was all true it was just one of several important facts which were not made public at the inquest. There were 800 lifebelts and 12 lifebouys on board but without exception those bodies wearing them were found floating feet upwards – they were either wrongly used, or of bad design.

There was no mention that the ropes of the lifeboats were firmly stuck to the davits by point, which meant that they had 10 be cut free to plunge heavily into the sea. This fact was later revealed by Richard Williams of Chacewater, who survived. A renowned Cornish wrestler and miner, from ater. he was returning to Cornwall from Pennsylvania, was forever after known as “Schiller” Williams. on deck as the vessel rebounded, only to strike more violently. Right over our heads we could see the glim-mer of the Bishop Lighthouse through the heavy fog, and hear the clang of the bell. Captain Thomas, an Englishman, but a naturalized German. was giving orders to lower the boats. This was almost impossible as they had been newly pointed, and the point had fixed them tightly to the davits.

The Captain’s boat was loss ered and was at last afloat, and they tried to launch another, but she was staved in during their efforts to get her out of the davits. and when she was cut loose, she sank, and from 50 – 60 men and women were plunged into the sea. I was washed from the Schiller and had to swim for dear life.

Boat after boat was swamped around me. I was in the water two and a half hours and at last was picked up by the Captain’s boat, in which there were 16 men and Mrs. Jones. We pulled around all night, shivering, and wet to the skin, picking up as many as we could find alive. Finally, we sighted a fishing boat and signalled her with Mrs. Jones cape. The fog had lifted, and we made for Tresco Island. A six-oared gig came out and towed us into the landing-place. (Gimble Porth).

I remained at Scilly a week after the Germans left. I used to go to the dead-house on Rat Island to identify the bodies that were washed, or brought ashore. Almost all of them had lifebelts on, and evidently these had caused them to be carried out to sea.” On his return to Chacewater a poet hawked a poem through the village about the wreck:

“How many Cornish were on board:

Their names we cannot gather.

But Richard Williams has been saved.

And his home is at Chacewater- .

In February 1876, the German Ambassador in London wrote to Mrs. Dorrien-Smith expressing the appreciation of the people of Germany for the kindness shown by the Scillonians to the survivors. This was followed, at Penzance that April, by the distribution of gifts from the Emperor and Empress of Germany. Mrs. Dorrien-Smith received a bracelet with the cypher of the Empress. and the coastguard officer and the coxswain of the lifeboat received gold medals. Others received medallions and bibles. It is also said that because of the compassion of the Scillonians in the Schiller tragedy, that Germany did not attack the Scillonian passenger vessel in either of the two World Wars. In Old Town churchyard is the towering obelisk of Penryn granite erected as a memorial to Louise Holzmeister, along with two other headstones. The large east window of Hugh Town church is also dedicated to her. The three mass graves have for long been covered with secondary internments, and there is a need for some form of memorial near that spot to remind us of the terrible death toll of the wreck of the S.S. Schiller.