Malcolm Gould brings us the technical aspects of extracting clay, the practical methods used and more than a bit of local colour. A most informative and entertaining read.

Historical Origins

The name “kaolin” Al2Si2O5(OH)4 is derived from “kao ling,” the Chinese for high ridge, because it was first found in such places in the Kiangsi province of China in A.D. 500. The Chinese method of using kaolin to make high quality porcelain remained a closely guarded secret until 1718 when it became known to the western world from the writings of a Jesuit missionary in China. He described the importance of kaolin in the manufacture of Chinese porcelain and a search began for a source of this substance in Europe. Some deposits were found in areas of Saxony and France but were not of good quality. The mineral china clay (kaolin) is found in partially decomposed granite, an igneous rock which in its original hard state, forms the prominent moorland tors of Devon and Cornwall. In some areas, partial decomposition of granite masses took place millions of years ago when pressure created by disturbances in the Earth’s interior forced hot acidic gases and fluids through the granite strata. This action changed the feldspar in the granite to a soft white powder – china clay, also known as kaolin. Other constituents of granite include quartz and mica.

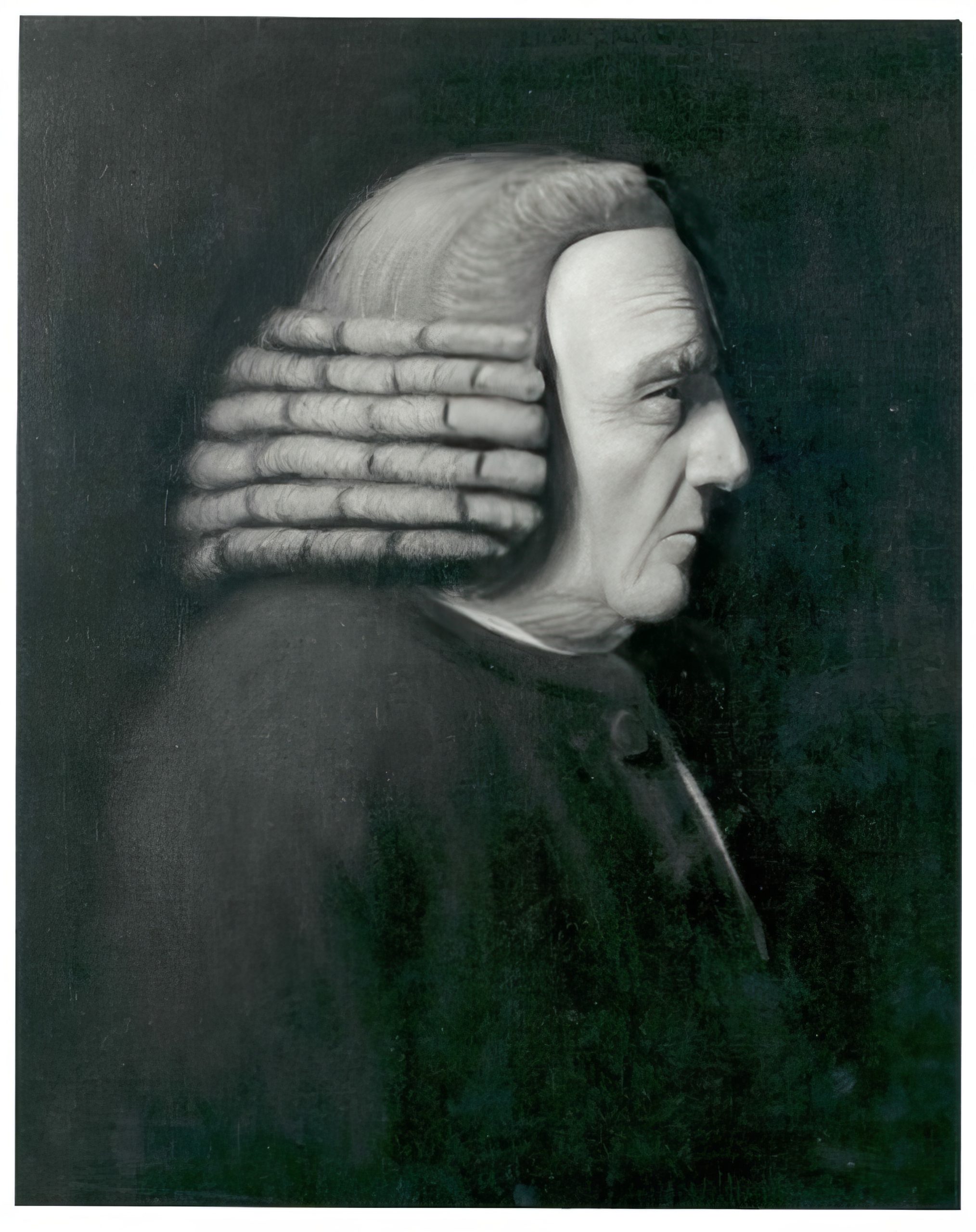

Amongst those searching for a source of kaolin was a Plymouth Quaker chemist and potter by the name of William Cookworthy. Whilst visiting a fellow Quaker in Penryn, surgeon Richard Hingston, who was also interested in the manufacture of porcelain, a visit was made to Tregonning Hill in the parish of Germoe, near Helston. Here, Cookworthy came across excavations and observed a white substance that was being used in making firebricks for smelting houses. He later wrote, “I first discovered it (Petuntse) in the parish of Germo, in a hill called Tregonning Hill. The whole country in depth is of this stone. The stone is compounded of small pellucid gravel (quartz) and a whitish matter, which indeed is caulin petrified (feldspar), and as the caulin of Tregonning Hill hath abundance”. On his homeward journey to Plymouth, Cookworthy stayed at St Stephen-in-Brannel, near St Austell, and here he discovered evidence of the extensive deposits of good quality china clay which are worked to this day.

In 1768, Cookworthy started a porcelain factory in Plymouth, which he later moved to Bristol. Following legal battles over patents, Staffordshire potters including Wedgwood, Spode and Minton visited Cornwall to secure leases on their own clay works but gradually, however, they withdrew from the clay producing area and the extraction of clay fell into the hands of local adventurers. By 1845 nearly fifty clay pits were being worked, and by the 1870’s there were some 120 separate small enterprises

The Process

The Cornish method of winning the clay has always been by washing it out of the kaolinized granite, “the matrix”. Once the clay source had been discovered by means of Prospecting Pits, removal of the over burden, sometimes ten to fifteen feet deep, was done by a team of men hacking through the earth to expose the bed of clay; the waste material was taken away in wheel barrows and horse drawn wagons. Water from a diverted stream would be allowed to flow down over the face of the clay pit and the matrix was first broken up with hand tools such as the dubber (a one-sided chisel-pointed pick) and the Cornish shovel. The washers wore leather “steamers boots” shod with irons made by the pits blacksmith and secured with donkey shoe nails. As a race, the clay workers of these pre-machinery days were probably the strongest men in the country; they reckoned to shift 20 tons or more of sand or clay in a day, with nothing but their arms and a shovel. Some men did nothing else for ten or twenty years; they toiled up the steep pit-face with their dubbers; in teams of three or four men breaking up the clay as they went. The diverted stream carried away the clay, it flowed down the slope or strake, which became steeper and longer as the pit was deepened.

Sand was caught in ground sand pits and the two sand men in these pits shared 1/3d (6.25p) per fathom (wages varied from each of the clay companies). The waste sand was hoisted in wooden tram wagons by a steam winder – the man on the burrow was paid the same as the sand men earned on fathom work.

They used either dubbers or two-pronged “ackers” in the stream. The local blacksmith sharpened the picks and dubbers (or even the carpenter, if he had time) however; when they got short the kettle boy had to take them to the smithy at Higher Nine stones to be “Laid”, i.e. have a length of iron swaged onto the short heel to restore it to its original length. One young man starting in the pit felt rather sorry for one little old man and left back the smallest lighter dubber for him. The old worker was most vexed and said so; he always had the heaviest dubber on the theory that “wance you got’n up there boy! ‘e’ll come down on is ouon”.

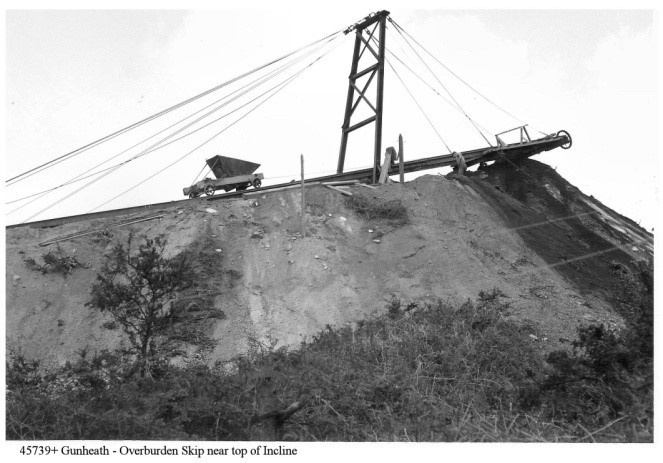

Criggan pit worked two shifts on what was called “a six-hour coose” (*). The forenoon shift was from 6.00 am to 12:30 pm with a half hour stop for crib and the afternoon shift worked similarly from 12:30 pm to 7:00 pm. When nature called, the men had to make do with their surroundings; the disused pit bottoms were overgrown in places and each man “had his own vuzzy bush” (gorse bush) behind which he relieved himself. It was considered to be most antisocial to use another man’s vuzzy bush. As the early pits were quite shallow; an adit was driven to allow the clay to flow along with sand and mica to the refining floors. However, as the pits became deeper, it was necessary to raise the clay, which was suspended in water, to surface. To achieve this, a pumping shaft was sunk through the un-kaolinized edge of the pit and a tunnel known as a level was then driven towards the centre of the deposit and a washing shaft sunk. Where the ends of the two shafts met and joined was known as the Button Hole Launder. The power was supplied either by a waterwheel or a Cornish beam engine. At the bottom of the strake the ground levelled out and when the milky stream reached this point it ran very slowly over the sand drags, pits known as “Patent Pits” that retained all but the fine sand. The waste quartz sand was loaded from the “Dogs’ Hole” at the lowest point of the pit and was raised to the top by a skip, by means of a steam or water powered winder. It was then dumped, forming the conical “White Mountains” or “Cornish Alps” locally known as “Sand Burras” that formed the mid-Cornwall landscape.

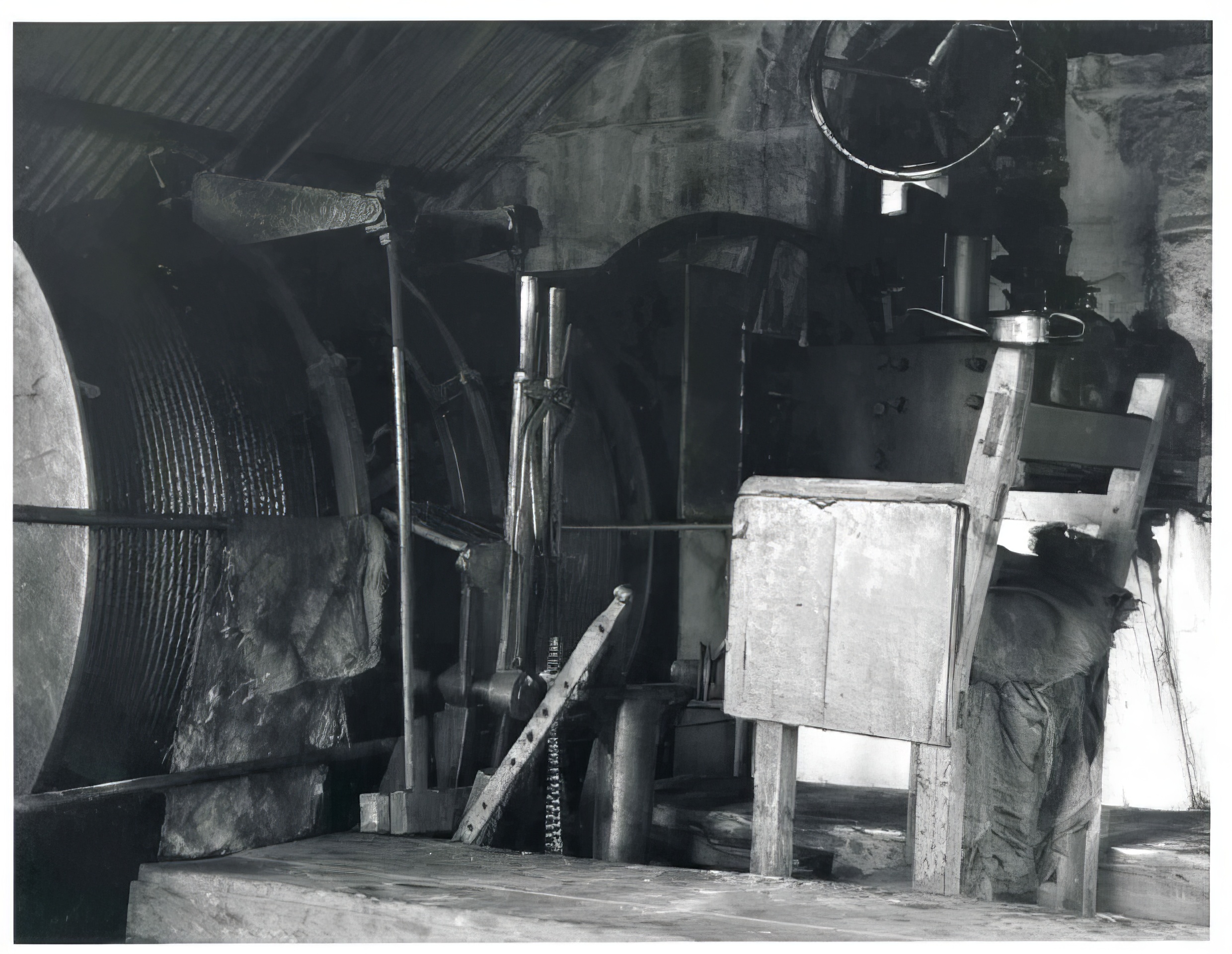

Skips were hauled by a winder; and a boy who at the age of 12 in about 1921, spent hours watching his father and his mate, both winder men, at work at West Goonbarrow Pit. The boy’s father’s workmate went sick so his father worked “doublers” to cover the emergency (often done to keep a workmate’s job open for him to come back to). The boy used to deliver his father’s dinner to work for him to eat between the two shifts, also “crib” for the second stint. The boy used to take over the winder while his father checked the fires and ate his dinner and had wound hundreds of loads successfully before the Captain came into the winder house and remarked, “That boy isn’t old enough to be in charge of a winder”. After that, his father had to manage as best he could.

Another method of shifting the waste sand in the clay works was by way of an aerial ropeway known as a “Blondin”. It worked on the gravitational principle, i.e. the full bucket pulled the empty bucket back up the incline rope. The ropes, of which there were two of each (each bucket ran on one and was pulled back or let out by another), worked on two drums controlled by one brake-band operated by a screw control. There were no indicators to guide the operator and when it was foggy many crashes resulted; the bucket coming in too fast and striking the turn wheel frames. The blacksmith would have to straighten the bucket frames after such crashes.

The sand from the Platt (*) was pulled up the incline by a single cylinder steam engine situated beside the main winder at the pit known as “The Hospital Platt”. It was where the lame and a few selected employees were put to work.

Wheal Rose pit, now infilled with mica, just north of the Bugle to Roche road at the front of Gracca Hill, was known as old “Whitewash Work”. The owner was known as “Charlie Whitewash” as when he tried to sell the clay pit, he got his workmen to whitewash the stopes to improve their appearance – Good old Charlie Whitewash!

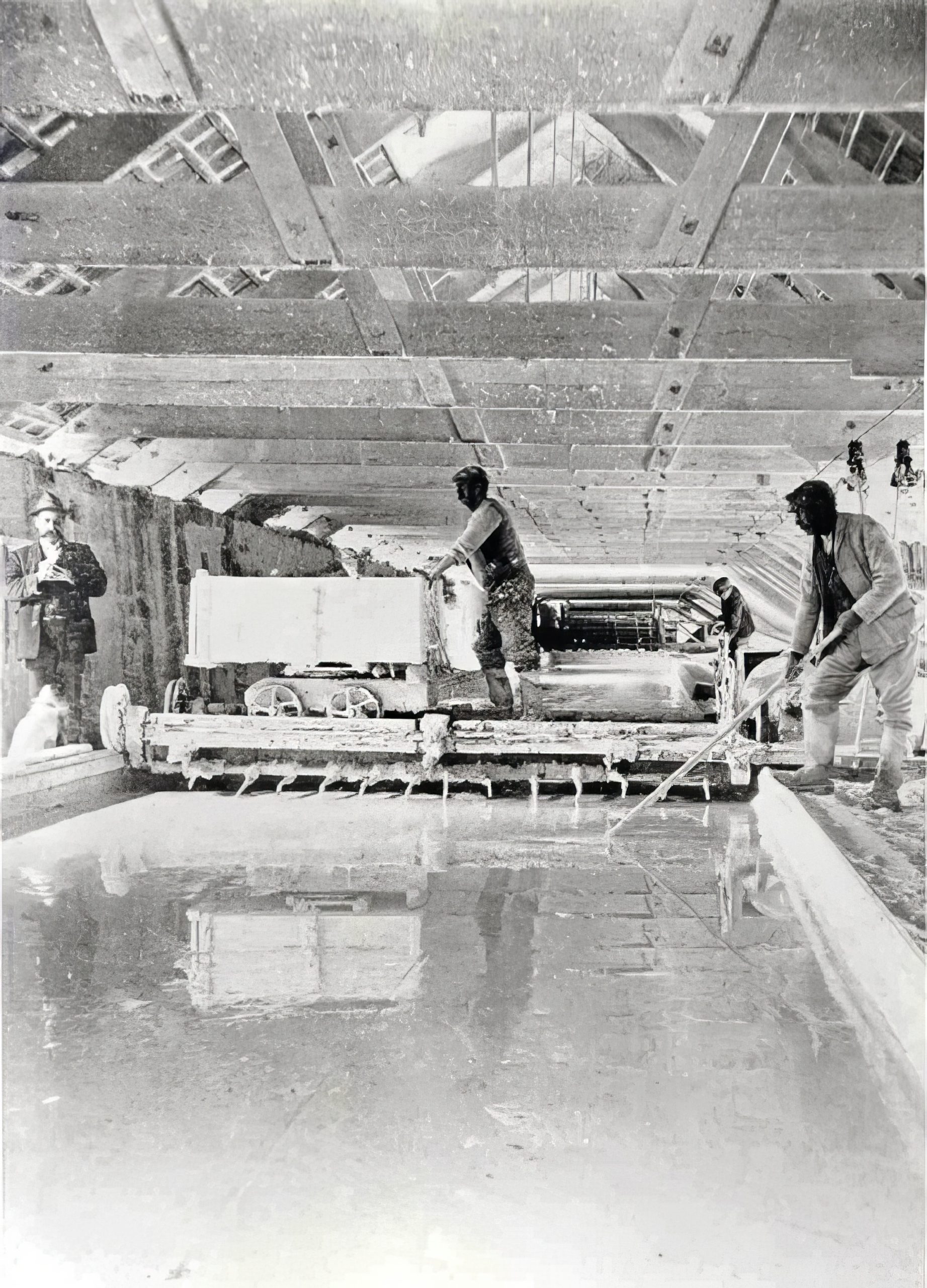

The clay continued its journey through the mica drags, long narrow channels of wood running parallel to each other, some 200 feet long. Here the mica was separated from the clay, the waste mica particles being heavier than the clay settled in the channels. Every eight hours or so, these channels would be scraped with “shivers” (*) the mica waste then “went to country” where it was disposed of into the nearby streams thus turning them white. The clay passed through a “Blueing house” (*) and was then turned into settling pits where the heavier clay particles settled to the bottom. The clear water was allowed to escape and after some hours the clay, now the consistency of cream, was turned into more settling tanks adjacent to the drying kilns. Here the clay was allowed to settle again until it was the consistency of thick clotted cream or junket. The kilns were coal fired and floored with fire-clay tiles over flues which ran along the entire length of the kiln. A typical kiln would be about 15 feet wide and some 300 feet long, the exhaust from the fires were then taken away by a chimney at the cooler end of the kiln. The clay was taken from the settling tanks to the kiln and spread to a thickness of about a foot over the very hot floors; drying would have taken from one to four days. The kiln men started at half-past five in the morning, when the kilns were hot, and they worked almost naked, the sweat pouring off them, until ten o’clock. They spent these four-and-a-half hours shovelling clay into the little wagons from the settling tank, pushing it along to the kilns about a hundredweight at a time, tipping it out and then shovelling it forward to the kiln. They worked in teams of six, four out in the tank filling the wagon and two inside, shovelling out the dried clay from the kiln. The outside men wore special long leather boots with wooden soles: they packed the insides of their boots with straw to keep their feet and legs warm while they stood in the wet clay. When dry, the clay was thrown over the side of the kiln into the linhay (*) which ran the entire length of the kiln.

An employee who, as a young man had worked at Tresarrett kiln [Bodmin Wenford mineral line] from the age of 14 and a half until he was 17, remembered the vast numbers of snakes that it harboured. They used to drop out of the roof in particular and, if they landed on one’s head or shoulders, the old men used to advise, “Lab’m boy, ee wont urt’ee if you lab’n vall off’ee natural”. A great number of snakes used to come down a stream close to the kiln at certain times. He remembered being there with his brother when they were school boys and using the clay scoop from the tanks to lift out the snakes and drop them on the hot plate of iron used to warm the pasties upon, thus killing 247 snakes in one season.

Transporting the Clay

In the early 1900s, a number of china-clay drying kilns were still not connected by rail to the main line, although sidings were being rapidly laid. A large proportion of the tonnage sold had to be transported by horse-drawn wagons from the kilns to the railway terminus. Each wagon carried five tons and was pulled by one shaft horse and two trace horses, the shaft horse doing all the manoeuvring. The wagoners worked in pairs and when the gradient was too steep, one driver would park his wagon well into the kerb with the shaft horse still attached, and his leading horses would be added to the other team; this was known as “doubling up”. The clay wagon was a peculiar and specialised construction, with a narrow wheelbase and only one brake, a foot-operated contracting band on the boss of one wheel.

At Bilberry, opposite the Minorca Lane junction near Bugle, there was “some fun” with the wagoners while shipping from this kiln. “Groser” was pulling out in a hurry with a heavily laden clay wagon of traditional design, in order that the next wagon in the queue could back in to be loaded, when his front wheel dropped down into a collapsed “Cundard” (*). Now, the front wheels of normal clay wagons were of much smaller diameter than the back wheels as they were fixed on a swivelling axel and required to be able to go under the bed of the wagon to permit a tighter turning circle. Instead of unloading, or jacking up the front of the wagon and packing under the front wheel, which would not need to drop far below ground level to be axle deep, Groser took the team from his son-in-law’s wagon, and double hitched it onto his own team. Then Mr Grose got up on the shafts, roused his double team, who lay into their collars and promptly sheared the pins and pulled the shafts off. “There was ructions!”

Tales from the “Crib” hut, or as you party down West may call it, “Croust” hut.

The Cornish Pasty

It was the job of the Kettle Boy to fetch and carry for the men in the pits and the dries, however his main task was to warm the pasties and boil the kettle for their tay at crib time. A chap who had worked as Kettle Boy at Gunheath Pit told me that after warming so many pasties, he could tell just by looking at them and feeling their weight whose pasties was whose!

As well as the clay men there were the engineers, one of whom would always go for his crib at least 10 minutes before the rest of the gang; the management got to know this and wanted to catch him out. Well, one crib time this particular engineer was eating his pasty when the other men came in to “stream off” (*) and eat their crib. He had already eaten about two thirds of his pasty when someone looked out and spotted a member of the management heading towards the crib hut. Heeding his warning, the engineer, in an instant, took the last remaining piece of his pasty, blew into the bag and replaced the remaining pasty uneaten side up. He started to nibble it slowly whilst exclaiming “this pasty is some hot”, well, he couldn’t have eaten it too fast as there wouldn’t be anything left and he would have been caught out. The fact is that the manager saw him go in at crib time and couldn’t understand how he couldn’t have caught him. However, this engineer was a good worker and whenever he had completed his task would go to one of his mates and say “can I give’ee a hand boy?”

One more before we go back to work:

At one of the engineering depots, we had a crib room where you would leave your crib on the table for the canteen man to have it warmed up ready by midday. Well, one chap left his pasty on the table, expecting the last man out of the canteen to slide the door shut. A chargehand often brought his dog to work, and it used to sleep in his little office and wander around the yard. Unfortunately, on this particular day, the door was left open and the dog got in and ate the pasty! There was ‘ellup but the next day in the crib room the conversation turned to the pasty, and the chargehand said, “I dun’t know what was matter with the dog last night, all he wanted to do was drink, I think there was too much salt in the pasty!” And that stirred it all up again.

Engineers:

One engineer, during his period in the tin and china clay industry, assisted in the installation and operation of several Cornish pumping engines, in particular one at the Trethosa clay pit. He told the tale of the first qualified, college trained, engineer appointed by the West of England China Clay & Stone Company. On one occasion when an engine had ‘run a bearing’ the new engineer arrived at the pit to see how things were going and found the local driver/handyman busy with his pocket knife shaving the new bearing to size, as he had done many times before. The engineer took the opportunity of giving some verbal assistance, discussing the number of thousandths clearance required, and various technicalities involved, etc. The engineman listened intently but without ceasing his operations on the bearing, and when the engineer had exhausted his lecture, he commented. “I don’t knaw a bit what you be talking ’bout Mister, but when I do fit a bearing he got to fit ‘xactly”. And needless to say, the bearing was eventually fitted exactly and work was resumed.

Excavators:

Gunheath pit borrowed a half-slew Ruston Bucyrus navvy from Treverbyn, about 3 miles distant, in about 1936 to take off, urgently, a piece of overburden across the north Westside of the pit under the nearby farmstead. Charlie Hancock (my great uncle) and Eddy Edwards came with it as drivers etc. It was a rope face shovel type that could turn only 90° to the left or right from dead ahead. They trammed the overburden from the face with Jubilee wagons and put in a winch behind the navvy with two spurs, one each side of it, a vast improvement on taking off burden by hand. This machine was driven by an internal combustion engine of sort.

However, this machine was also borrowed by other works and on one occasion it was required at Hawks Tor Pit up on Bodmin Moor some 25 miles or so from the St Austell clay district. The only way to get it there was to track it and it was seen tracking through Bugle Square at about three or four miles an hour on its way there. There were no low-loaders in those days and it might have taken two or three days to make the journey. A brave old way!

Well Pards, that is about all fer now. But just a few days ago, a young engineer came to where I work at Drinnick, and I said to him; “Boy, I feel bleddy old, you’m the third generation of your family of engineers who has worked in the clay works; I worked with yer granfer, yer father and uncles and now you!” It used to be common for boys to follow their fathers into the clay works but not so much these days.

And if you come to Wheal Martyn museum, I’ll tell’ee a few more tales.

Glossary:

Coose: a work shift

Platt: a level area

Shivers: timber

Blueing house: where a blue dye was added to the clay stream after it came through the mica drags, this was a form of giving the clay more brightness, a bit like our mothers and grandmothers would have used; a blueing bag that was put in the wash to make the whites brighter.

Linhay: a building which appears to lean against another

Cundard: drain

Stream off: wash

References:

CCHS: China Clay History Society.

John Tonkin: archive CCHS The Story of China Clay: CCHS Publication, ECC Publication.

RescorlaReview. The History of ENGLISH CHINA CLAYS: Hudson

Malcolm is a Cornish Bard (Map pry gwynn). He has worked in the china clay industry at Imerys, formerly English China Clays, for the last 46 years. Having grown up in the clay district it was the thing to do. He became a member of the China Clay History Society not long after its formation, volunteering at the archive and being asked to understudy one of the members, Harry Woodhouse, Cornish Bard, who looked after the film archive. With work commitments it was difficult to attend the archive on weekdays so he now volunteers at Wheal Martyn Museum in meeting and greeting, giving guided tours and driving an old 1934 ERF lorry. He also visits local groups giving clay related talks and showing films from the archive.

This wonderful article was previously published in Cornish Story – Click Here to read more