Travelling west on Cornwall’s main artery, the A30 road, the sometimes bleak, sometimes wild, but always beautiful expanse of Bodmin Moor begins, a short distance from Launceston. About eight miles from that ancient gateway to Cornwall, and situated off the A30 is the parish of Altarnun. Many years ago, this little hamlet was known as Altar Non, the name having derived from the Altar of St. Non or St. Nonna. This pious lady was one of the many Celtic missionaries who passed through Cornwall in the 6th and 7th centuries. St. Non was the mother of the patron saint of Wales, St. David, and it is she who is the patron saint of this picturesque little village. A stroll through this hamlet is strongly advised. The abundance of flowers decorating the hedges and gardens of the picture postcard cottages are worth the trip if for no other reason. The village war memorial stands in its own bed of colour, and it is this that draws the eye and mind, to the history of this hamlet, typified by the ancient church standing just over the stone bridge, in its shaded, peaceful grounds.

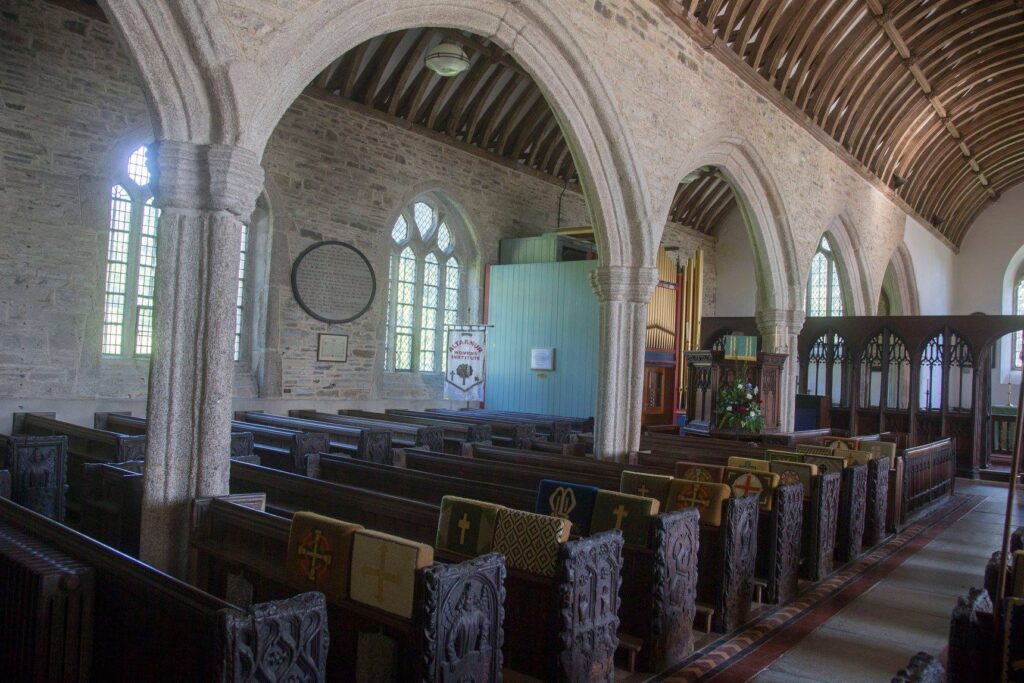

Enter the churchyard through the decorative wrought iron gates, and wander up the gravel path, towards the south porch and main entrance to the church. Old grave stones are on each side of the path, the inscriptions legible, despite the moss, lichen and ravages of the weather that has swept the valleys form the high moors for many a long year. Look for the stone that was carved by one Nevil Northy Burnard, with a nail! He was perhaps not surprisingly to later become a famous sculptor and at the height of his career, carved a marble bust of the infant Edward, Prince of Wales (son of Queen Victoria). After the tragic death of his daughter, Burnard lost interest in his work and in life generally; returning to his native Cornwall, he was sent to a Redruth Workhouse, where he died. The tower of the church at 130 ft. is reputedly one.of the highest in Cornwall, and it is this that gave rise to the Cathedral of the Moors name often applied to this church. Entering the sanctuary of the church itself through the south porch, the Norman font can be seen to the side. This square, 12th century baptismal receptacle has faces carved on each corner, and a radial motif between, very typical of this period. The aisles are very spacious for a church of this size, and the roof is supported by pillars formed from single blocks of granite.

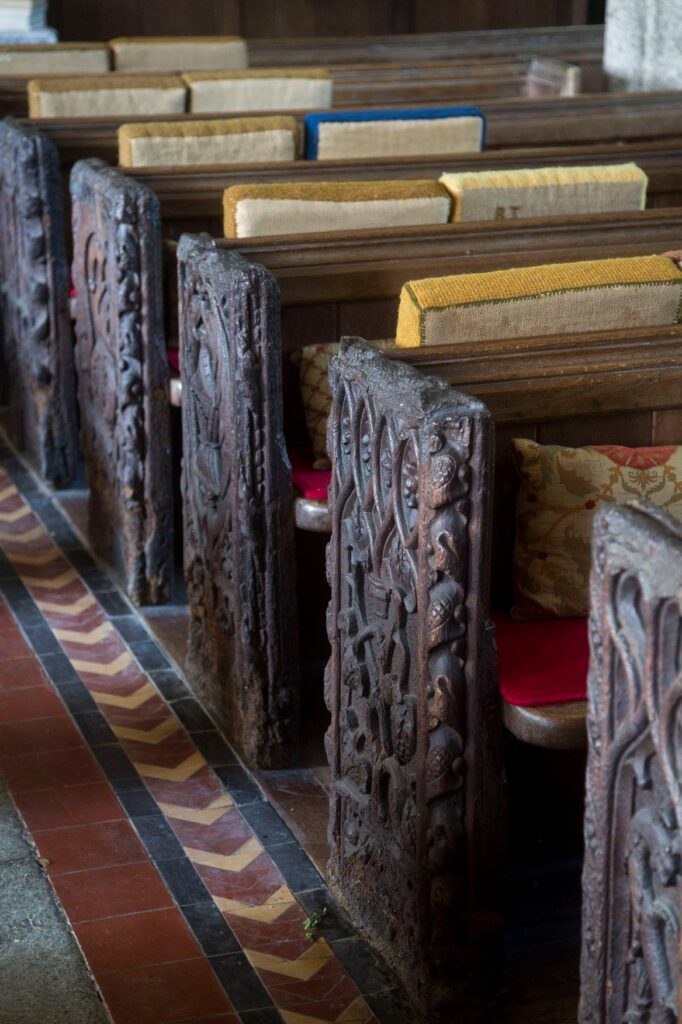

Of particular note are the carvings on the pewends, 79 in all, and each with a different design, some depicting Christian symbols, some showing aspects of local life. All are the work of one Robert Daye, and were carved between the years 1510 and 1530 (as is signed on one of the benches near the font).

The nave is separated from the chancel by a particularly striking screen, a splendid example of Gothic styling, a little battered by the ravages of time, but nonetheless beautiful. Step into the chancel and kneel beside the communion rail which runs the whole breadth of the church, and read the inscription carved on the rail: “John Ruddle, minister of this Psh. Anno 1684. William Prideaux and Sampson Cowl, Churchwordens”.

The paintings behind the altar date from 1620 and though the colours are faded, the crucifixion and a portrayal of the Lord at the altar, are still clearly visible. Pass down the north aisle and look into the vestry.

There can be seen a fragment of the old building , built into the wall, about two feet from ground level. This was once a capital from one of the original pillars in the old Norman Church, and when the present church was built, this was used as a building block.

At the end of the entrance is a magnificent tower. It holds a ring of eight bells, and when rung, they can be heard for many a mile across the vast moors that envelope Altarnun.

Outside again, mention must be made of the grave of Digory and Elizabeth Isbell, who in 1743, were the first people to entertain John Wesley, the great preacher and founder of Cornwall’s religion, Methodism, when he first visited Cornwall. Leaving this moorland church, pause and look back at the Celtic Cross, built in the 6th century. It does perhaps remind us of our own frailty, but as well, serves as a monu-ment, to our heritage, which we in Cornwall strive to preserve, and of which we are so proud. Then reader, leave this little parish and rejoin the bustle of the 1990s, but hopefully a little better for having visited the ‘Cathedral of the Moors’.