For 150 years the light from the Bishop Rock lighthouse has warned the mariners to steer clear of the rocks or “fangs of Scilly”. The Bishop takes its name from the steep sided pinnacle rock on which it is sited. In medieval times the rock and its surrounding satellites were known as the “Bishop and clerks” from their fancied resemblance to a bishop sitting in conclave with his clerical advisors. There is a more grisly side to its reputation in the middle ages. In those days, the islands were under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Exeter and the only court on the islands was the bishop’s which of course was an ecclesiastical court. The sentences at such courts were lighter than those at civil courts and the death penalty was never imposed. The court managed to extract the supreme penalty for crimes such as murder by sentencing those guilty, to be taken to the Bishop’s Rock and there left with a loaf of bread and a pitcher of water. There is no record of anyone ever escaping alive from the Bishop.

The first Bishop Rock lighthouse was an open framed metal structure built in 1849, but swept away in a storm in 1850 before it could be used. The second structure was built of Cornish granite from the De Lank quarries and dressed on St. Mary’s before being taken out to Rosevear, the nearest inhabitable island to the rock. The stonemasons and others lived and waited until the seas were sufficiently calm to approach the rock and assemble the previously shaped and dove-tailed blocks, rather like a giant Lego set. It was decided to set the lowest stone seventeen feet below the high-water mark and it was said that the engineers had to wait three years, leaving a gap at the base until conditions were right, before this key stone could be fitted. This was finally accomplished towards the end of 1853, but it was 1858 before the lighthouse was completely finished and ready for service. When it was at last completed, there was a ball on Rosevear. The St. Mary’s town band was rowed out to supply the music; the hutted accommodation and the workshops were decorated; guests, including ladies in their ball gowns, from St. Mary’s and the other inhabited islands. danced the night away. All that remains amidst the seagulls on Rosevear today are the foundations of a couple of huts.

Even the second Bishop Light was not safe from the ravages of the sea. In 1881 blocks of granite, weighing more than half a hundredweight each, were torn from the side of the lighthouse which was described as “swaying in the hurricane winds”. It was decided to reinforce it with an outer case of granite and to add four more storeys, increasing the height from 120 to 146 feet. Once again, the stone was cut and dressed at the back of St. Mary’s quay, before being taken to Rosevear and out to the Bishop.

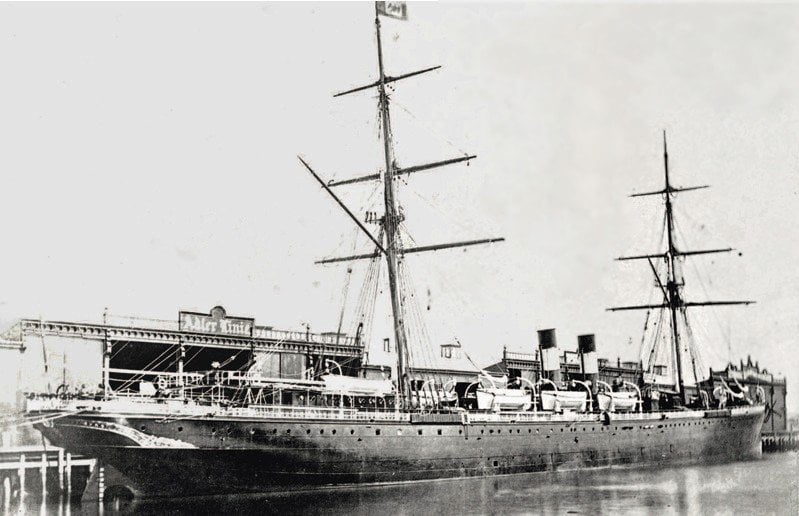

Nevertheless, there were still wrecks around the Bishop, the most heart-breaking being that of the German transatlantic steamer, Schiller, on 7th May 1875. In thick fog and squally weather, she passed nearly half a mile “inside the Bishop”, instead of steering outside the rocks. She was wrecked on the Retarrier Ledges with the loss of 335 lives. In 1901 another wreck literally left her mark on the Bishop. The four-masted barque Falkland, on 22nd June, in clear, but rough weather, was unable to avoid the Bishop and her main-mast struck the tower of the lighthouse. The scar is still pointed out by boatmen to today’s visitors on trips round the Bishop.

In 1976 a helicopter landing pad was built on top of the light house and in 1994 the lighthouse was fully automated, and the keepers were taken off.

There are many amusing stories from the time the lighthouse was manned. The keepers stayed on the lighthouse, sometimes for months at a time. Their bunks were curved, being built to the contours of the walls. Sleeping in them was a quickly acquired skill, the body curling round. Unfortunately, it often took some time for the keepers to adjust to the matrimonial bed on their return to their families. Many wives complained that “It takes him at least a week to straighten out and learn to sleep in an ordinary bed!” Keepers had to take their own food with them to the light. During the tourist season supplies would be taken out by the tripper boats and hauled up to the keepers by ropes. For some years there was no cobbler on Scilly and people wishing repairs would take their shoes to Nance’s shoe shop, where they would be boxed up and sent to the mainland. Unfortunately, there was a mix-up on the quay and the surprised keepers, expecting mail, newspapers and a few goodies, opened a parcel containing thirty pairs of shoes, all in need of mending. Sadly, the weather then broke up and it was three weeks before the shoes could be recovered for sending to the mainland.

Lighthouse keepers were a special breed, some of them decidedly eccentric. One of the Bishop’s keepers a few years ago became addicted to golf and thought that the helicopter pad would make a marvellous practice tee. Taking a set of balls with him, he was filmed driving them off the top of the light. His craze did not last long, as there was no means of retrieving his balls.

Boatmen have taken trips to the Bishop for years and told yarns about it. One of my favourites concerns the little old lady, who asked a boat-man why the Bishop flashed white and the Round Island light flashed red. He replied, “Well, my dear, it’s like this. Round Island uses pink paraffin and the Bishop uses white oil.” She appeared completely satisfied with the answer!