In the first of this series Tony Mansell has chosen the village where he grew up and for which he still has fond memories.

There is nothing very remarkable about Silverwell: (1) nothing that makes it stand out in any way. Like most villages, it’s seen its share of good and bad times with the odd tragedy thrown in. There’s been a bit of mining there but mostly it’s farming country, mixed farming – arable and dairy.

In times past, folk were probably born and died in the same village. They went about their business, raised their families and, of course, went to chapel. That’s apart from those who trudged up the hill that leads out of the village to attend the Anglican Church, that’s Mithian Church or the Church of St Peter. Apparently it was to have been named Silverwell Church but that village’s mine was struggling and it seems that the Church of England didn’t want to be associated with anything in decline.

My family moved to the village in 1951, when I was five years-old. The first question we were asked was, “Are ee church or chapel”. I guess my parents must have pondered over that one as theirs was a mixed marriage: Mum was church and Dad was chapel. Of course, that was when the Methodists were happy to call their place of worship by its true name – a chapel. Nowadays that word is a bit down-market but as one well-known Methodist minister said, the church is the body of people and the building is a chapel.

Silverwell is a scattered village community with no discernible centre and visitors across the years have struggled to find its main features. It straddles the civil parish boundaries of St Agnes and Perranzabuloe, a line mainly defined by a small river which begins its journey in a field just below the Church. It passes through Silverwell Moor, now mostly drained, and down through some lovely valleys to the Atlantic at Perranporth.

The origin of the name is uncertain but Charles Dysart Teague, sometime owner of Silverwell Mine, states in a mining report of the 31st October 1903 that the mine was named after the village and not the other way around. He goes on to say “In old times hearling (hurling) (2) was a big game in the county. It is said, in one of those games they lost the silver ball in this valley, it was afterwards found in a well and from this it took the name of Silverwell”. I guess that I would have preferred something derived from Kernewek (Cornish language) but that’s all we have so we’ll go with that.

As I said, the village was heavily reliant on agriculture and my father worked at Greenacres Farm. The sounds and smells of farming were always present but there were no complaints in those days, it was natural and somehow less objectionable than today, besides, there were fewer incomers (3) to complain. I often watched my father milk the cows, each one with its distinctive name. The clanging of the metal churns is still in my head, it is evocative, a memory that doesn’t fade.

We lived at Lilac Cottage: it was tied (4) to Greenacres Farm. It was quite large and whitewashed on the outside. I have fond memories of growing up there in a happy household. Of course, being a tied cottage, if my father had lost his job then we would have lost our home – a bit precarious but I don’t remember it being a problem. Of course, it may well have been through my parents’ eyes.

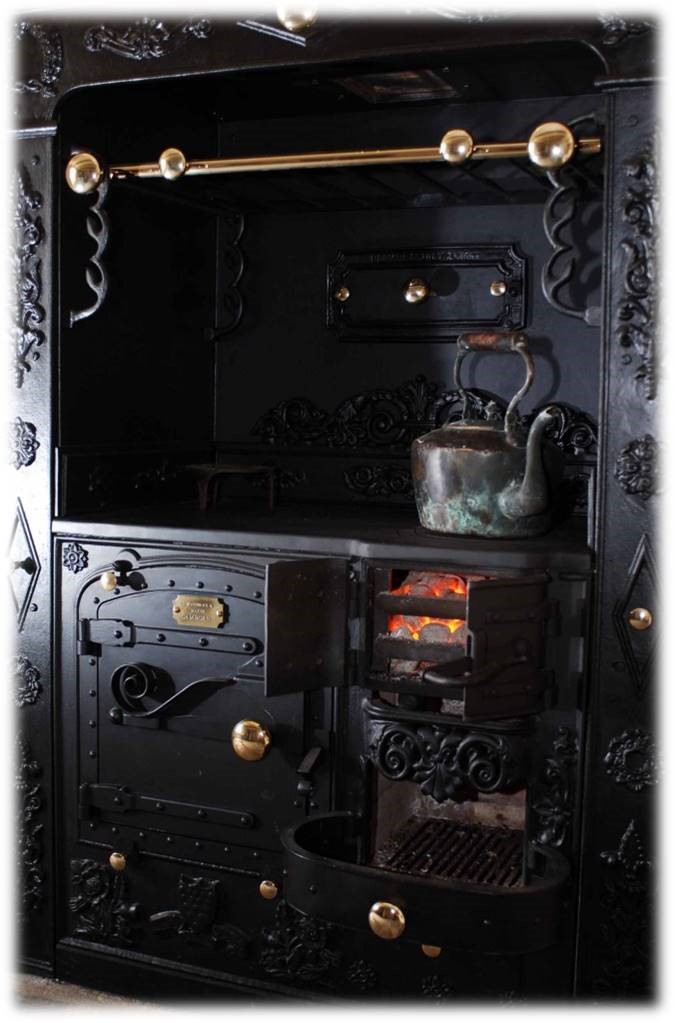

The kitchen was the heart of the house, with a Cornish Range, (5) large Belfast sink, huge table and canvas on the floor. The food was always good: the heavy cake, pasties, bread & butter pudding, apple pie, under roast, saffron cake, rabbit pie, buns and, of course, the bowl of simmering milk on the stove, none of that bought in clotted cream trade for us. Neville Paddy, my cousin, has fond memories of ‘Cornish Gold,’ (Cornish cream) from when he worked at Silverwell Dairy during the 1950s. He recalled, “The milk was poured into enamelled bowls and placed on the Cornish range until the cream rose to the top. It was covered with muslin and left to cool on the slate slabs in the dairy and when the crust had set, and the cream’s consistency was such that it did not drip from an upturned spoon, it was skimmed off. My father always enjoyed his with bread and treacle (thunder and lightning), my mother preferred hers on a Furniss’s gingerbread and Edward Lawrence [Silverwell Dairy] liked it on porridge or on slices of freshly picked tomatoes. My own favourite was on warm ginger sponge but a special treat was a piece of honeycomb topped with clotted cream…ansum.”

The purists will notice the error here of using a scone rather than a split

(Yeast-leavened bread rolls, which are split when still warm and spread with jam before topping it with a generous dollop of clotted cream)

Most of the cottages in the village were built of cob (mud and straw with a few stones thrown in) with very little foundation and roofs of salvaged timber covered with slate, cement-washed many times over the years. Although the walls were probably a couple of feet thick the damp managed to find its way in. Layers and layers of wallpaper and Kotina (polystyrene) did its best to keep out the moisture but, at best, only disguised it.

Before the arrival of the television our sitting room was little used – it was reserved for high days and Sundays but once ‘the box’ was installed it became an everyday room. Our first television was just 14 inches (350mm); it was powered by an electric generator and had a rolling, flickering screen that would be switched off in disgust these days.

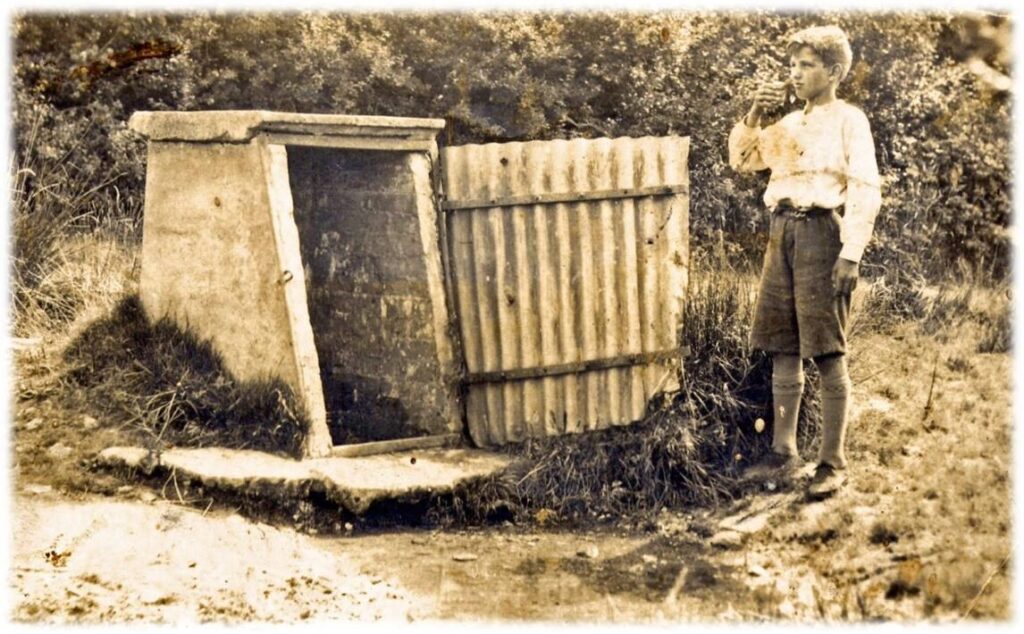

Our lavatory was in the rear garden, an old stone building with a slate roof. If you needed a light then you took a candle but that only confirmed the presence of spiders – huge black ones that still haunt me. At first, our facility was a bucket and chuck-it job but after a while we did graduate to a flush toilet and cesspit. A great day in our family’s history was the installation of a bathroom complete with bath, basin and toilet. The old tin bath was consigned to the rubbish heap and the ritual filling with kettles of hot water became a thing of the past. One of our neighbours, not known for suppressing her opinions, thought an indoor lavatory to be disgusting.

At first we had no mains water supply and we had to rely on a well with a hand-pump with which my brother and I had to fill the buckets. It was a tad rickety and needing priming before it would oblige. That involved pouring water down the upturned spout to fill the pipes otherwise we were simply pumping air. Those living at the other end of the village could use the old village well or make a trip “down chute”, a launder (gutter or channel) delivering a supply from a nearby stream.

The arrival of an electricity supply in the late 1950s was a great step forward. Prior to that we could only imagine the luxury of flicking a switch to illuminate a room. It was ironic, too, that Silverwell was crossed by giant pylons taking electricity to almost everywhere – except to us! We were grateful when it did arrive though but the candles and oil lamps were kept in reserve just in case. Perhaps it had been the lack of good lighting that helped ensure that we went to bed on time, “Up timberin hill,” as my dad used to say.

When I was a little older I worked on the farm during the school holidays and at weekends when I fed and mucked out the pigs. I still have a fondness for them. They were housed in sheds around the yard, all having access to a field. I also helped with the harvest but I don’t recall it with the nostalgia that I often read about; it was hard work. Despite that, there was always time for a bit of humour and when local chaps Chris Parris and Charlie Williams were working in a field, Charlie suddenly asked Chris if he had seen his waistcoat. “You’re wearing it,” said Chris. To which Charlie replied, “‘Tis a good job you told me otherwise I’d ‘ave gone ‘ome without ‘n”.

It is said that Silverwell once had a shop but, that apart, most things were brought to our door. Butcher Bray of Penstraze brought the meat, Stanley Cowl of St Agnes the bread, Mr Murrey of Chacewater delivered the papers and George Symmons of Mithian the groceries. Les Shugg called with paraffin and Harry Thomas of Trevellas kept the wireless running with his accumulator charging business. Arthur Benney was the greengrocer and prior to him it was Raphael Thomas with his horse and wagon. Mrs Rashleigh, a gypsy lady from Radnor, sold pegs and Mr Rashleigh, presumably her husband, travelled the area selling canvas offcuts for floor covering.

Growing up in a 1950s Cornish village was idyllic: riding our bikes, playing in the streams, running in the woods and nicking apples from a nearby orchard. I don’t know why we did that, the owner was a friend and would have given us as many as we wanted if we’d asked. I guess it added to the excitement; it was what boys did.

Just a short distance from where we lived, and down a typical Cornish lane, was the Methodist chapel. Silverwell Wesleyan Society built their place of worship, sometime around 1900, on the site of a previous Wesleyan chapel which was in a dangerous state and had to be demolished. In the late 1890s the people of Silverwell submitted an application to the Wesleyan Chapel Committee in Manchester to build a new chapel. It stated, “There are 65 regular hearers out of a neighbour population of 200”. One of the questions on the form asked if it would be in the midst of a poor or middle-class population. The response was, “Farmers and Labourers”. Like so many chapels, the building work was undertaken and paid for by local members and there was much consternation when it was discovered that, when completed, ownership would pass to the Wesleyan Chapel Committee with no compensation. For years after, local farmer Edward Lawrence complained, “They took it away from us”. When the chapel first came into use it had 70 let seats and 50 free seats. As late as the 1950s, pew rent was set at two shillings and sixpence per person per year. The chapel was somewhat isolated, so much so that one preacher failed to find it and returned home. The lane in question continues its way to the small area of Whitestreet and was once a main thoroughfare: in the mid-1800s it was the route for funeral cortèges journeying from Mithian Village to St Peter’s Church. Over the years many hell-fire Methodist preachers kept the congregation awake with their sermons. I remember some who certainly put the fear of God into me and, I must say, painted a picture of a being to be feared rather than loved.

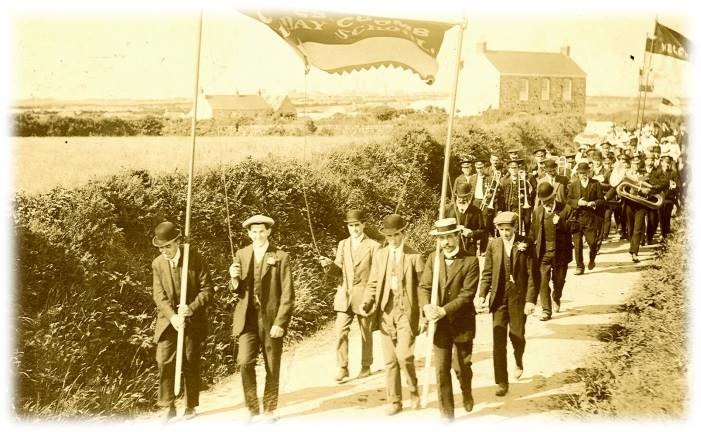

Tea treats (6) were held at the end of July; always a happy occasion and one of the most important on the village calendar. At the head of the procession was the banner, carried as a proud demonstration of faith. Then it was back to the field for fun and games and, of course, the famous tea-treat buns. Silverwell Chapel closed in 1982 and before long it was converted into a dwelling: having known the place so well that still seems strange to me.

So much of my young life revolved around the chapel; that was the way it was in rural communities. Like most youngsters I saw the services as a chore but now, looking back, it means more to me than when I was young. It was a part of my growing up and I have warm recollections of the people who attended there.

Silverwell Lead Mine was actually called Wheal Treasure but it seems inappropriately named as no fortunes were ever made there. J H Collins, in his book ‘Observations on the West of England Mining Region’, described it as, “A mine often prospected, but never with success”. According to Cornish mining historian Jack Trounson in one of his books it had, “A most extraordinary little stack”. It was actually quite ungainly and consisted of an old iron boiler tube approximately three feet in diameter and about 25 feet high, secured in position by four chains. On top of this was an eight feet high brick cap which made it look top heavy. The mine seems to have been last worked shortly before 1914 when a small amount of galena (lead sulphide) was extracted but Jack Trounson’s comment said it all, “It did not contain enough lead to make earrings for a black-beetle”. During the 1920s the young Chris Parris and his friend, Will Angwin, were not adverse to a bit of mischief. They filled the old firebox with furze and wood and set fire to it. They then toured the village spreading the word that the mine had opened up again. When, during the Second World War, the stack was demolished the iron was used in the manufacture of armaments.

There are many who mourn the Silverwell of old, the tight-knit community where you knew everyone. Where much of the work was on the doorstep, the entertainment was home-produced and the chapel central to the way of life. In many ways it was little different from any other Cornish village. It had its characters, its folk who were always ready with a bit of gossip or a touch of scandal, spread more efficiently than the pages of the West Briton.

Silverwell has changed over the years; the farms modernised, the cottages improved, the chapel no longer a place of worship. But the biggest change is in the people; the culture is different and the accents of 50 years ago are sadly missing. Those people helped shape our lives and the community gave us values. I regret that my children do not share its memories.

- Silverwell is a hamlet in Cornwall approximately 4 km south-east of St Agnes and 2 km north-east of Blackwater.

- Hurling is an outdoor team game played only in Cornwall. It is played with a small silver ball. The game has similarities to other inter-parish games, but certain attributes make this version unique to Cornwall. It is considered by many to be Cornwall’s national game along with Cornish wrestling.

- Incomer is a person who has moved to live in an area in which they have not grown up, especially in a close-knit rural community.

- A tied cottage is a dwelling owned by an employer and occupied by an employee: if the employee leaves their job they usually have to vacate the property; in this way the employee is tied to their employer.

- The Cornish Range was a stove manufactured by various Cornish engineering companies and blacksmiths. Often nicknamed the ‘slab,’ they could be temperamental to use but were often claimed to bake the best pasties. The various attachments were of brass and the amount of that material was thought to represent your wealth and status.

- Tea treats were annual religious gatherings comprising a parade, a Cornish tea, games, and, of course, the tea treat bun (large saffron bun).

Tony Mansell is the author of a number of books on aspects of Cornish history. He was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He is a sub-editor with Cornish Story and a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive specialising in Cornish Brass Bands and their music. This article and many others is featured in the Cornish Story website.