The fascinating story of Joseph Antonia Emidy has been mostly gleaned from the autobiography of one

of his pupils, the Cornish-born politician and slavery abolitionist, James Silk Buckingham, who wrote

about Emidy’s life up to 1807. Others have written about him, mostly using Buckingham’s material, and

their work may provide a more comprehensive picture of this remarkable man than is possible in this

short article.

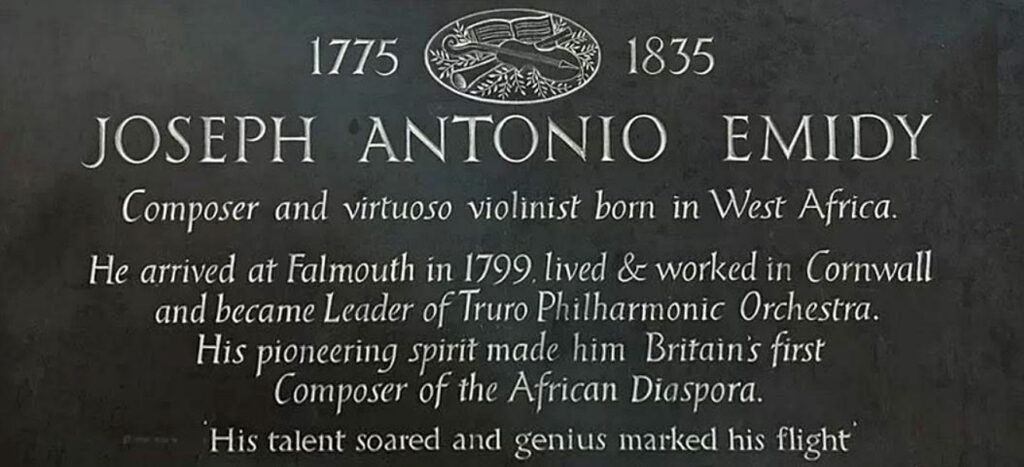

From these accounts we know that Joseph was born in 1775, in Guinea, on the west coast of Africa.

At the age of 12 he was sold to Portuguese slavers. An abhorrent practice viewed through our 21 st century eyes but a common occurrence in his time when slaves were valuable merchandise. He was transported to Brazil and sold to a slave master where he remained for a few years. It is suggested that it was here that he learnt to play the fiddle, possible taught by his slave master although he is also said to have been “Taught by Jesuit Priests”.

While still a young man, probably about 16 years old, we find him in Portugal where his master observed

his musical talent and arranged for him to receive violin lessons. With instruction, he became a proficient

violinist, good enough to gain a position with the Lisbon Opera.

We cannot be sure how long he held this position but it was brought to an abrupt end by the British Navy

when in 1795, HMS Indefatigable under Sir Edward Pellew, put into Lisbon for repairs.

James Silk Buckingham wrote:

“While thus employed, it happened that Sir Edward Pellew, in his frigate the Indefatigable, visited the

Tagus, and, with some of his officers, attended the opera. They had long wanted for the frigate a good

violin player to furnish music for the sailors dancing in their evening leisure, a recreation highly favourable

to the preservation of their good spirits and contentment. Sir Edward, observing the energy with which the young Negro plied his violin in the orchestra, conceived the idea of impressing him for the service. He

accordingly instructed one of his lieutenants to take two or three of the boat’s crew, then waiting to convey the officers on board, and, watching the boy’s exit from the theatre, to kidnap him, violin and all, and take him off to the ship. This was done, and the next day the frigate sailed; so that all hope of his escape was vain. Poor Emidee was thus forced, against his will, to descend from the higher regions of the music in which he delightedly – Gluck, Hayden, Cimarrosa and Mozart, to desecrate his violin to hornpipes, jigs and reels, which he loathed and detested; and being, moreover, the only Negro on board, he had to mess by himself, and was looked down upon as an inferior being, except when playing to the sailors, when he was of course in high favour. As the captain and officers judged from his conduct and expressions that he was intensely disgusted with his present mode of life, and would escape at the first possible opportunity, he was never permitted to set foot on shore for seven long years [probably four years]. He was only released by Sir Edward Pellew being appointed to the command of a line-of-battle ship, L’impetueux, when he was permitted to leave in the harbour of Falmouth, where he first landed and remained, I believe, till the period of his death.”

In his book, Music in the West Country, Stephen Banfield questions Joseph Emidy’s place of birth and

whether or not he was kidnapped by a press gang. He does say, however, that he was probably tricked into joining Pellew’s ship.

This latest experience of captivity lasted until 28 th February 1799 when he was discharged at Falmouth

where he chose to remain.

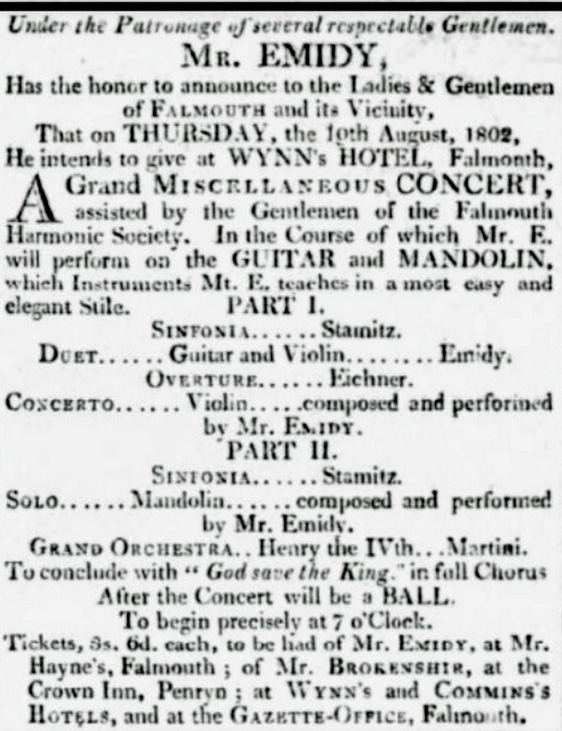

Now, having to earn a living, he began a musical career providing lessons, concerts and other musical

events. An advertisement in the Royal Cornwall Gazette of the 7 th August 1802 stated that he taught piano, cello, clarinet and flute as well as guitar and mandolin “in a most easy and elegant style”.

He was also the leader of the Falmouth Harmonic Society and had begun composing: his concerts included much of his wide-ranging work.

Joseph was probably making a reasonable living, good enough to consider marriage, and in September

1802, he married local girl, Jenefer Hutchins, the daughter of a local tradesman. In July of the following

year, Jenefer gave birth to their first son, Joseph.

In 1804, Flushing born James Silk Buckingham began taking flute lessons with Emidy. Perhaps

Buckingham’s love of learning the flute could be explained by his comment:

“… finding it a most agreeable recommendation in female society, of which I was always fond.”

Of Joseph he wrote:

“An African Negro, named Emidee, who was a general proficient in the art, an exquisite violinist, a good

composer, who led at all the concerts of the county and who taught equally well the piano, violin, violoncello, clarionet, and flute.”

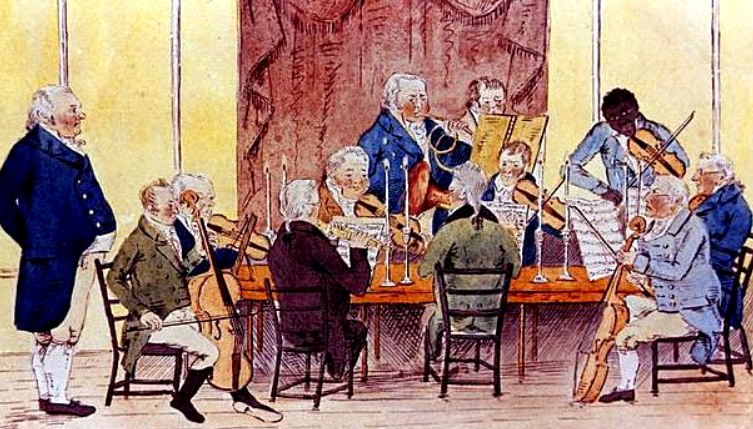

Buckingham had remarked that Emidy played to a degree of perfection never before heard in Cornwall and this ability also impressed a later admirer, William Tuck, who came into contact with the composer as a member of the Camborne Harmonic Society.

“This predilection (for music) was evinced at Camborne in my early youth when a few gentlemen combined to meet for musical study and recreation once a fortnight, and engaged a professional from Truro as teacher. This preceptor was a Mr Emidy, an African Negro. This remarkable man was the most finished musician I ever heard of, though I have had the privilege of listening to most of the stars who have appeared on the London stage during the past 50 years, but not one of them in my estimation have

equalled this unknown Negro. He was not only a wonderful manipulator on the violin, cello or Viola, but

could write fluently in either of these clefs; his hands seemed especially adapted for the work, his

extremely long, thin fingers were not much larger than a goose quill: where this great talent came from was always a mystery to me, and to all who came in contact with him.”

Truro’s first Biennial Concert and Ball was held in 1804 and Emidy took part in it. He was also involved in

the second, in 1806. The programme for Truro’s third biennial concert, in 1808, included overtures by

Handel and Martini and a violin concerto by Emidy himself.

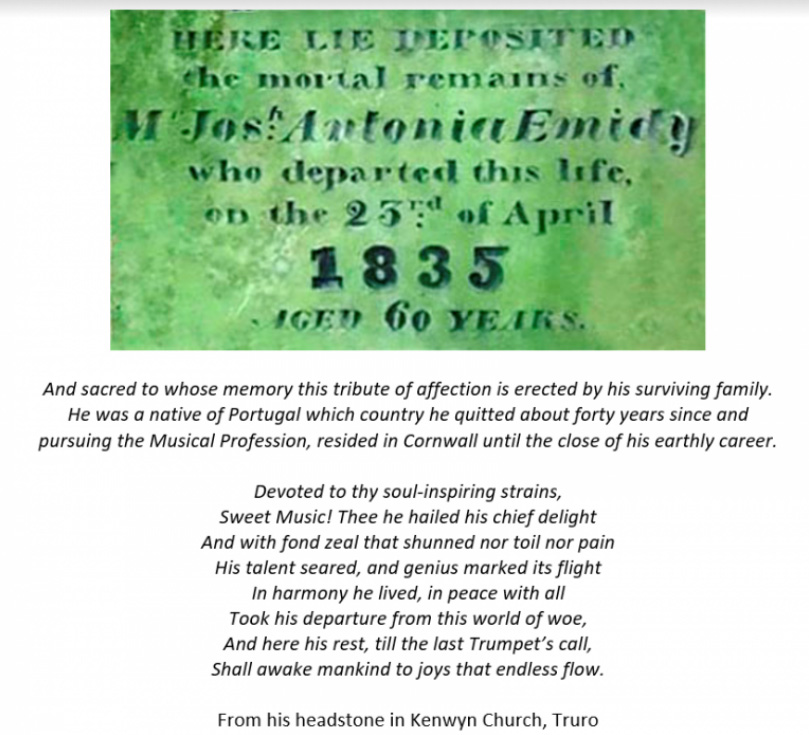

Joseph and Jenefer’s second son, Thomas, was born in July 1805. He became a composer and leader of a

quadrille band. A further son, James, was born in 1808 and one report suggests that they had a total of

eight children.

The reputation of the black slave musician spread beyond Cornwall thanks to the efforts of James Silk

Buckingham, who took some of Joseph’s compositions to London where they were well-received.

James Silk Buckingham wrote:

“Emidee had composed many instrumental pieces, such as quartetts, quintetts and symphonies for full

orchestra, which have been played at the provincial concerts and were much admired. On my first leaving

Falmouth to come to London – about 1807 – I brought with me several of these pieces in manuscript, to submit them to the judgement of London musical professors, in order to ascertain their opinion of their

merits. At that period, Mr Salomon’s (sic) the well-known arranger of Haydn’s symphonies as quintett, was

the principal leader of the fashionable concerts at the Hanover square rooms. I sought an interview with

him, and was very courteously received. I told him the story of Emidee’s life, and asked him to get some of his pieces tried. This he promised to do, and soon after I received an intimation from him that he had

arranged a party of professional performers, to meet on a certain day and hour at the shop of Mr Betts, a

musical instrument maker, under the piazza of the Royal Exchange, where I repaired at the appointed time, and in an upper room a quartett, a quintett, and two symphonies with full complement were tried, and allwere highly approved. Though Salomon was sufficiently impressed to suggest that Emidee should come to London to give a concert of his works, others felt his colour would be so much against him, that there would be a great risk of failure: and that it would be a pity to take him from a sphere in which he was now making a handsome livelihood and enjoying a high reputation, on the risk of so uncertain a speculation.”

The Royal Cornwall Gazette in June 1810 provided a glowing report of a concert performance of his music

with equal acclamation for its composition and its execution. Such reports were becoming increasingly

frequent.

By 1812, Joseph and Jenefer had a growing family and they decided to leave Falmouth and move to Truro

where Joseph became the leader of the Truro Philharmonic Society – from 1816 to 1826.

His advertisement in the West Briton of December 1820:

“Violin, Tenor, Bass-Viol, Guitar, and Spanish Guitar taught, balls and assemblies attended,

harps tuned and piano-fortes buffed, regulated and tuned.”

His Concerto for French Horn was played in a concert in December 1821 by the Royal Cornwall Band but now, two hundred years later, we are left to wonder what a gem of the musical world this probably was.

Thanks to Tony Mansell CLICK HERE to see the original on cornishstory.com