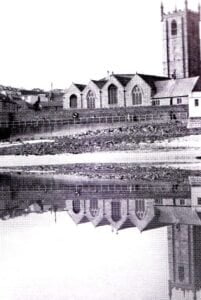

Being born and reared in St. Ives, the writer has been brought up, like so many others, with the story passed down from generation, that the stone for St. Ives parish church was brought from Zennor by sea. Our own Saint Ia is surrounded by myths and legends regarding her arrival here all those many centuries ago. Like Saint Piran she came by sea from Ireland, and the story has it that he floated into Perranporth on a “millstone”, but Saint Ia came ashore in St. Ives bay, on a “leaf’. Many now suggest it was most likely a coracle, this being in features likened unto a flimsy leaf. However, to inquire for hard facts relating to the transportation of stone from Zennor by sea to St. Ives, is indeed a challenge, which one trusts, can be answered if not by the written word, then by the belief that there is no smoke without fire. If one could go back in thought and time to the opening years of the 1400s, and stand on that carp now known as Eagle’s Nest in the Parish of Zennor, what would one behold? To start with, there would have been no buildings such as we see today – the more modern style house built in recent times, and the former Zennor Poor House, which once catered for Napoleonic prisoners of war as a fever hospital. Looking towards the coastline the field pattern undoubtedly would be similar to that of today. Indeed this coastal plateau has changed little in a thousand years or more. Populations have increased and declined over the past six or seven hundred years, with the land giving forth of her bounty, and mild winters, to failed harvests. and long spells of severe weather. With initial mineral discoveries and the ability to work surface deposits of tin, and the later advancement of underground mining, the population of this parish increased to what many found hard to believe. The early census records give proof of what the village of Zennor, its hamlets and farms supported by way of a great “working” population. Days in which there was not any work meant no money for food, clothes or a roof over their heads. This was often brought about by a mining failure when sometimes a whole neighbourhood would be on the move, either to the next parish, or another land, in search for a livelihood. Returning to the 1400s we find that farming was the main occupation in the parish of Zennor. There were of course the other trades and skills which gave men their sustenance. We have viewed the sea-ward elevation from this cam, but what of the hinterland? This too holds its fascination, as it is the hills and downs that still keep their secrets today of bygone trade routes and ancient monuments. The terrain has changed little, but one difference being evident would have been the sound of hammers ringing from amongst those cliffs and hills. We come now to these tradesmen – the stone-cutters, their product and its transportation from bed-rock to a magnificent granite church at St. Ives.

Photo, Thanks Tony Smith

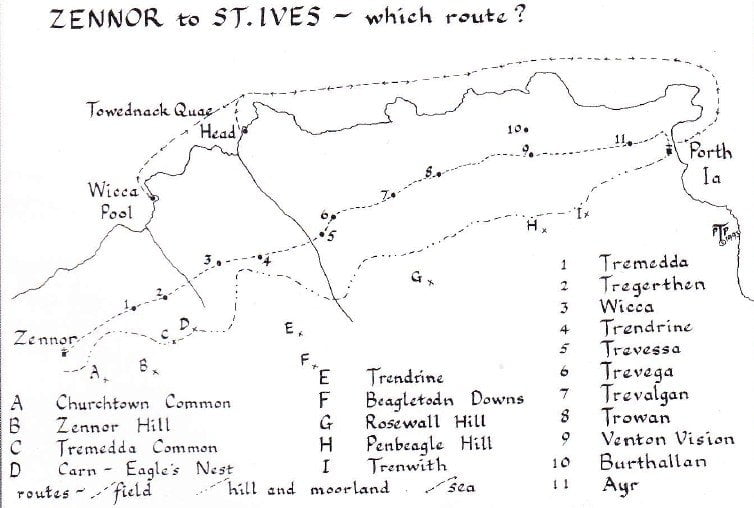

. The age old craft of extracting, working and dressing the various granites of this locality had been passed down from father to son for generations. This was the natural way of crafts and trades continuing, particularly in country areas. Indeed some men had more than one skill, as there was not always demand for one product continually. Stone-cutters of five hundred years ago were no exception to this rule and they too could turn their hand to tin-streaming, or whatever was needed to keep body and soul together. Today, the methods of those stone-cutters would appear primitive, but what they produced is for the discerning eye to see; still functioning, whether it be a hewn gate-post, granite trough or the quoins and lintels of the many cottages and farm buildings, these surely having survived the test of time. When a large amount of worked stone was required, then other stone-cutters from surrounding parishes could be found only too willing to help undertake this much needed work. No doubt this was the case when such a large quantity of stone was necessary for the building of St. Ives parish church. The volume of granite involved for just the impressive tower is as follows:- approximately 2_500 dressed granite facing stones for the exterior. and a similar number for the interior. How, then was all this granite transported from its cleaving out of the bed-rock, and dressed all square and true? One must remember in that day, there were only field paths linking the homesteads, and rough tracks across hill and moor. Horses were few and far between, as later muster rolls reveal. Oxen teams were limited to sometimes only one in a parish. At the farm and hamlet today known as Trowan. we gather, from the Cornish language, that around this period it was known as “Trevowen” – farm of the oxen. A farmer might have had his own bullock for working. but it was mainly the hands and strength of the man himself. with only a shovel to break in the land. In the main then. stone was transported locally on a wooden sledge (skid) dragged along, either by the men or whatever beasts of burden that could be procured. To transport a large individual stone or a load of smaller stones over land to St. Ives, would involve a long arduous journey. If an oxen team were to be used from Zennor to St. Ives for this purpose, it would not take just a few hours, but at least a full day or even longer, and then there was the return journey to consider. The flat lands being no doubt the easiest route to take would have to be negotiated in the summer after there had been a long dry spell. Wagons were heavy and wheels were made of solid wood, an axle could easily snap with the jolt of its heavy load passing over just a small outcrop of rough terrain. From Hellesveor there then would be the downhill journey to St. Ives. With the knowledge of the state of the Stennack “Tin Ground”, seemingly being turned over constantly for the means of extracting its alluvial wealth, one could well image the wagon master continuing along the flatlands to Burthallen and down over Ayr to Barnoon. Off-loading the stone there, it could be “skidded” halfway down what is now called Barnoon Hill, to a ramp up to the steadily growing tower. Alternatively to the long haul overland, there is the other route by sea. This has always appeared the most practical and logical mode of transportation. Creation has decreed that tides flow up and down this stretch of coast twice, each and every day. In fine summers, which most probably they had then, boats from St. Ives could sail. rows or drift down on the ebbing tide, towing rafts, to collect stone laden rafts and returning to St. Ives with the flood tide. During long, fine summers, this procedure could continue day time and also through its short nights. The journey to and fro taking no more than twelve hours, and only the exertion at some time of rowing. One would imagine the stone being hewn handy to its cliff top departure, travelling down over a ramp to be loaded onto rafts grounded at about half tide mark. On arriving at St. Ives and being beached in “Saint la’s Cove”, the stone was ready to be used, as and when it was required. The location of the point of departure of this Zennor stone, has been regarded by many as to have been from Towednack Quay Head. This gives the impression of a former quay there, but this is doubtful. The original wording on old maps is Towednack Quae Head; the “Quae” has been quoted to me recently, by one acquainted with the Cornish, as probably meaning “hedge”, but that is another story. Where then could this stone have been loaded for its sea journey? Five hundred years ago the coastline and cliff from Gurnard’s Head to Wicca was not as we see it today. In the past, surface mining spoil, dumped over a cliff, could soon form a slope which would be suitable for lowering stone to its base. Over the years, since mining ceased, this spoil would have been eroded away with weather and sea action to appear today as the original cliff. Little wonder, the church building took sixteen and a half years to complete. The stone-cutters of Zennor, together with the blacksmiths, whose skill in the making of the tools and sharpening of the same, would surely have worked flat out to supply the stone necessary for such a large undertaking. The tower alone is nearly one hundred feet in height, but one must not overlook the construction of the aisles. These contain a mixture of building material, from sea-worn “blues” to killas and a variety of granite, the suggestion being of more local origin. The source of this granite most likely coming from the Worvas and Penbeagle Quarries, taking the Belyars Lane and Skidden Hill route into the town. Hard facts of these I have none, but if Hick’s manuscript, which has been lost for 150 years, were to be rediscovered it could well reveal facts about the building of the church. Or is the proof lying on the bottom of the sea bed somewhere between Zennor and Porth Ia? It is hardly likely that every single stone made the complete journey. A lost one or two could have hitched a fishing trawl net, or snagged many a mackerel line over the years, or is it waiting for some skindiver to locate a stone and then reveal the truth!