How things have changed since Richard wrote this article in 1996, there are now numerous sightings of the Cornish Chough in Cornwall. We will give an update as soon as an expert lets us have an article.

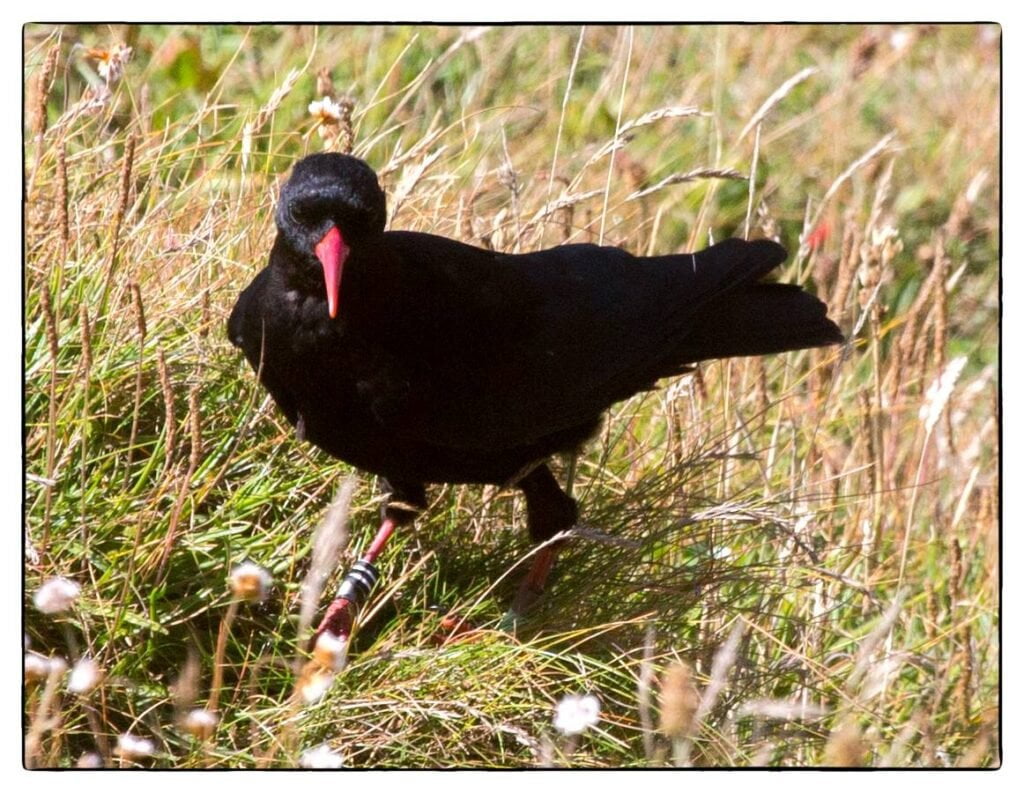

Three endangered species stand upon the Cornish crest: the fisherman is threatened, the tin miner is virtually extinct, and the third, our national bird and Britain’s rarest crow, has gone… but forever? When the last lonely chough died near Mawgan Porth in 1973, England could no longer claim the species either. It might be common on official insignia, shop-fronts and business logos but the chough in Cornwall can now be seen live only at Paradise Park, Hayle. The nearest wild birds are in Pembrokeshire and Brittany. With none in Cornwall, these populations are isolated from each other. At Padstow in the seventies and eighties, we kept choughs for breeding. We wanted to restock the coastline but there were puzzles. Why did this harmless bird, held in high esteem throughout recorded history -appearing on all manner of heraldic devices – retreat steadily during the nineteenth century from Kent to Cornwall? Why did it survive in Wales? What was different? Pembrokeshire is 100km. away, even as a rare crow flies. What would they find here if they did come? In short, can Cornwall support choughs today? It would be blatantly wasteful to release birds if the landscape could not support them, so we had to find out. This simple question led me into a five year study (core-funded by Paradise Park) with Glasgow University. Field by field I surveyed 200 kilometre-squares in Wales and Cornwall and then compared the data with the tithe maps of the 1840s to gauge changes over time. It became apparent that the big differences of a century and a half before diSappeared. So what had changed? A post-industrial revolution agriculture had profoundly affected the habitat and as the chough retreated west, it found no agrarian island refuges in Cornwall as it did in Wales and Brittany, nor a sympathetic agriculture as it did in Ireland. By 1910, Cornwall had become its last outpost in England. Choughs living across Europe and Asia do not need coastal lands but here the species is an icon of the Celtic fringes. At the north-western extremity of its range, the chough needs frost-free conditions where its invertebrate prey stays active all winter. But as the miners went so did their crofts and their animals which had nurtured this prey and which, by grazing the clifflands, allowed the choughs access to it. The chough is something of a conundrum, by turns shy and elusive then tame and confiding. It exploits pastoralism but shuns modern farming. Unlike other crows, it poses no threat yet its fate was hastened by ignorance, confusion with its cousins and, in its spiritual Cornish home, by egg and trophy hunting and taking for pets. The rarer it became, the more it was sought, for the wild once remote cliffs steeped in Arthurian legend, were the very places to which newly mobile Victorians were attracted. Then like harbingers of the ancient Celtic king, as I planned my work, ten years ago, two wild choughs returned, not to Tintagel but to Rame, west of Plymouth. I watched them all winter until one – sick with gapeworm (syngamus) – was taken by a peregrine. Its lonely mate drifted away and was lost until a tip-off from the late, much lamented, T.O. “Bob” Darke led me to a steep pony-grazed field in mid-Cornwall where it was last seen. It was on course for Wales. Hopefully it made it back. While with us, they provided unique data – fleshing out old anecdote about English choughs. It is folly to apply, uncritically, information about sedentary species from one region to another. Data from the Hebrides differs markedly to that from North Wales, which differs to that from West Wales. On Islay, choughs forage over grazed pasture but in West Wales, three-quarters of feeding time is spent on the actual cliffs. Permanent pasture is often reduced to an indeterminate zone between cliffs and an “improved” agricultural hinterland. The cliff complex (old clifftop grazing and cliffs) in my study occupied 85% of chough time. Not only that, but they fed more efficiently there too. So, as in prehistory, the wild landscape is crucial. Atlantic gales prune the scrub while the Gulf Stream promotes invertebrates. The optimum habitat is where grazed or eroded slopes roll down to stable south-facing cliffs. Extensive mixed farming with rough-grazing will compensate for poor quality cliffs and is certainly important in times of climatic hardship. “Untidy” and eccentric farming (traditional?) provides all manner of opportunities. Such labels reflect a human perspective but they help to illustrate the chough’s ability to exploit benefits afforded by man. It is often stated, even by ornithologists, that the chough merely requires “short grazed turf’ but in West Wales they use this for only 5% of time. More than 25% is spent on bare earth. Short grass allows access to the substrate but is not, it itself, a resource. However, pastoralism benefits the chough’s prey of earthworms and beetle and fly larvae, and ants – which are vital during breeding. The best habitat is a mosaic of vegetation and bare earth. Paths and trampled areas are used in Wales which, like Cornwall, attracts many walkers. Opponents of re-establishment claim that tourism is harmful, and so it is where insistent disturbance near a nest site interferes with incubation of feeding but this is rare because choughs nest early in the. year.. In fact, heavy cliff walking occurs only during the middle of the day during high summer when the birds are least active. At other times, wildlife has the cliffs and pathways to itself. By alternating feeding grounds or droppings down the cliff-face, choughs avoid walkers easily, usually without being noticed, even by bird-watchers! By using a variety of techniques to identify habitat components, it is possible to create favourable habitats. For example, faecal evidence showed that earthworms and cereal grain are interchangeable as a source of winter protein. Cereal grain is preferred probably due to the lower collection costs since it is surface gleaned but if this is not available, as in pastoral areas, earthwoiins can be substituted. To re-establish a lost species provides some respite for beleaguered conservationists, and reclaimed territory for a besieged nature. But it is important to plan carefully, monitor developments and protect existing populations, In nature nothing can be predicted with certainty but given that sufficient habitat is available, that prey species are diverse and abundant, and that land-use practices and human society is sympathetic, there is no reason why the chough cannot return. Islands provide the greatest length of multi-faced coastline relative to landmass. Their chough with young in derelict building on Islay in the Hebrides. Photo: Martin Withers absence off Cornwall worked against chough survival but with the above provisos, their importance recedes. A convoluted peninsula provides exposures and headlands. In Cornwall, such exists from The Lizard round West Penwith (in some respects virtual islands) and among tracts of the Atlantic coast well into Devon. The Rame birds – which survived for many months – showed that there are also other pockets of habitat. Scientifically, the chough is a biological indicator of a healthy and diverse cliff ecosystem. Since it is unlikely that enough choughs will arrive in the same bit of Cornwall at the same time, a breeding programme, “Operation Chough”, is underway at the Rare and Endangered Birds Breeding Centre at Paradise Park, but they are social birds and not easy to breed. It is recognised now that a Cornish population would help both Welsh choughs and the relict Breton population by providing a genetic bridge. With the National Trust’s active support (as the main coastland manager) and the enthusiasm of all national and local conservation organisations, it might come back unaided. But without a burgeoning population in Wales, will it bother? I suspect that if we are to hear the chough’s haunting cry or see its exhilarating aerobatics over our cliffs again, it will need some help. If we can reclaim this emblem, might it not help the Duchy and, in some curious way, those other endangered species too?