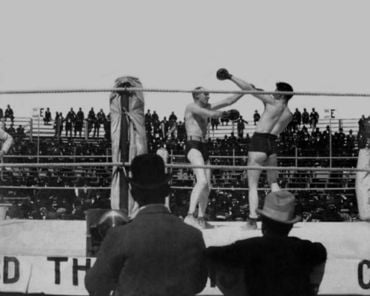

It was a match that had been five long years in the making. Four thousand lucky boxing fans managed to descend on Carson City, Nevada to be there in the flesh, but the world too had a seat at ringside. Thanks to the cameras of the Kinetoscope Company, Bob Fitzsimmons was set to square up to “Gentleman Jim” Corbett in a since legendary heavyweight show-down that would prove the first official fight ever captured on film.

Neither of its stars was about to disappoint. Already, the build-up to that historic century-old meeting of March 17, 1897 had seen both men fashion a script straight out of a yet-born Hollywood.

In the half a decade he had kept the pretender to his world heavyweight crown waiting on a shot, American James J. Corbett had played for every inch an archetypal champion – on the one hand, justifiably disdainful; on the other, perhaps, just a touch running scared. And Fitz? Well, Fitz – like all good challengers – had come out of nowhere.

Had he stayed in his native Helston, where a commemorative plaque still adorns the walls of the modest terraced cottage in Wendron Street where he was born in May 1863, the fiery Cornishman might have followed an number of familiar, if not infinitely less distinguished, careers. One can picture a lifetime spent plucking tin from soil, just as easily as mackerel from the sea, or drunks – like his father, the local town bobby – from the gutter.

Instead, when Bob was just nine, the Fitzsimons family took the fateful decision to suddenly up sticks and emigrate to Timara, New Zealand. For young son Bob a new trade soon beckoned – a trade that was to shape, quite literally, a pugilistic “freak”.

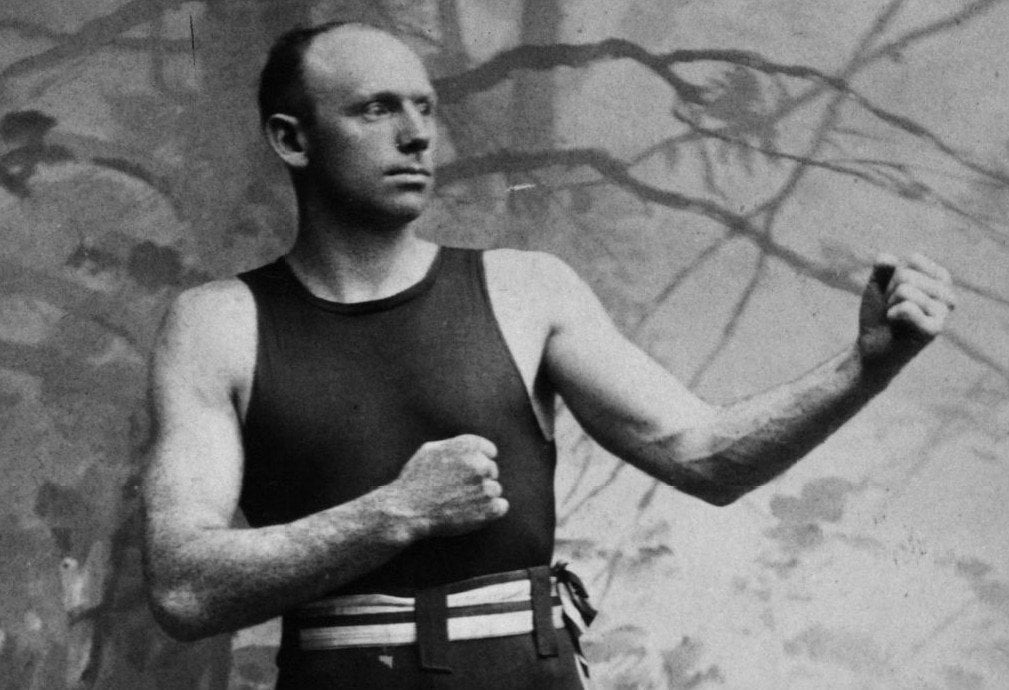

As an apprentice blacksmith, Fitsz’s gangly 11 stone frame rapidly too on the appearance of the anvil he so strenuously worked. Immense shoulders and a barrel chest made for some awesome upper-body strength, but below his long tapering waist, it was all perched on so spindly a pair of legs that he later had to wear padded tights when appearing in touring stage shows. Indeed, as the ringside artist Aquila Kempster, wryly commented: “Above the waist he heavyweight, below a spindly lightweight.”

Bigger opponents, who tended to underestimate as a result, invariably learned the painful error of their ways. At just 15, bare-knuckle fights were already proving a lucrative source of extra pocket money for the apprentice blacksmith. A year later, an old fighter named Jem Mace, who was touring New Zealand with his boxing circus, recognised the young man’s potential and tried to persuade him to go to the United States.

It would be eleven years, however, before Fitz took up the suggestion. Even when he turned professional and moved to Australia in 1883, the blacksmith – who practised his trade as part of his training regime throughout his career – had a hard time seeing the fight game as much more than a supplementary income to his true profession. Indeed, when he finally set foot on American soil on May 10th, 1890, it was with a little better than patchy record of predominantly exhibition bouts behind him.

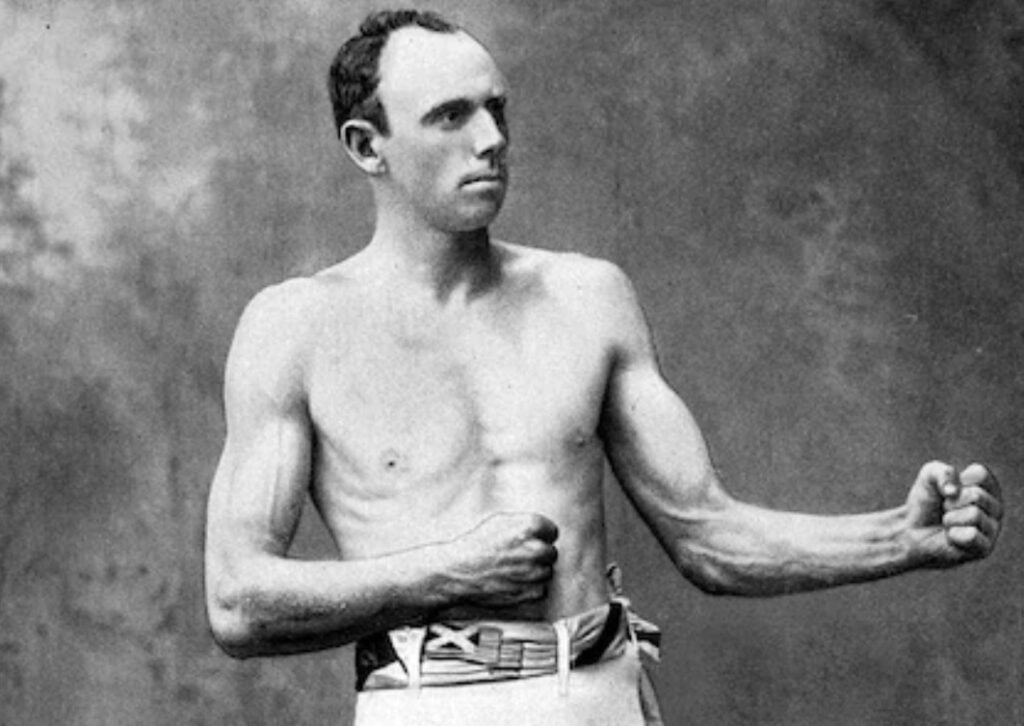

Just eight months later and, remarkably, the inexperienced Cornishman found himself in the ring with a living legend – not Corbett this time, but Jack “The Nonpariel” Dempsey. Sure, fighting as a middleweight Fitz had taken a few good scalps since his arrival in the States, but next to Dempsey’s record, it was as nothing. Through a seven-year reign as undefeated world middleweight champion, the Irish-American (real name: John Kelly) had earned national hero status and an aura of invincibility.

The pre-fight betting had only one winner, and it was assumed Fitz would have to content himself with the loser’s share of what amounted then to the largest purse ever for a glove fight. After the weigh-in, Fitz sportingly offered a hand, saying: “May the best man win, Jack”.

The champion responded with only a dismissive: “He will!”

He was right, of course, but neither he nor the crowd who packed The Olympic Club, New Orleans, could have believed just how so. In boxing terms, what followed was cool, calculated annihilation. In the 13 rounds before Dempsey lay sprawled unconscious on the canvas, Fitz had the champion down a staggering eleven times – repeatedly, though unsuccessfully, entreating him to quit.

When the one-time legend finally came round, he was led to his dressing-room, weeping all the way. “It wouldn’t hurt so much had I been beaten by an Irishman or an American,” he sniffed. “But to have it handed to me by a ****”* Englishman has killed me!”

His animosity towards Fitz was to mellow somewhat, however. On his death bed just four years later, Dempsey’s reputed dying instructions to his wife were to bet everything she could on Fitzsimmons every time he fought. Whether Mrs. Dempsey followed her husband’s advice, history is unclear – a more lucrative investment, however, she doubtless would have been hard-pressed to find.

For never one for complacency, having taken the middleweight crown, Fitz had his sights set on bigger fish. To be precise, he told the world he was confident of taking the reigning heavyweight champ “Gentleman Jim” Corbett. The American’s reaction was predictably unruffled. “Me, fight a middleweight?” He is reported to have commented. “No-one would pay a dime to see it. Tell him to stick to his own class.”

Despite his destruction of Dempsey, it was a sentiment many fight fans couldn’t help but share. Not only was the Cornishman too light, he just didn’t look the part of a growling heavyweight. Indeed, there was none of the “Dark Destroyer” or “Iron Mike” noms de guerre for Fitzsimmons. His balding head and fringed red hair, coupled with a skin covered in freckles, lent the eminently unintimidating nicknames “Ruby Robert” and “Freckled Bob”.

Fitz himself took not the slightest notice of his detractors. In his entire career, he only fought somebody lighter than himself once. Indeed, as he later explained in his most famous remark, made before a come-back fight against the sixteen-and-a-half stone giant Ed Dunkhorst: “The bigger they come, the harder they fall.”

Many would come, and many would fall, before Fitz finally got his shot at Corbett. The proud Cornishman even followed the advice of taking U.S. citizenship in an effort to hurry the match along, but the champion proved an elusive defender of his title. At one point, in fact, Corbett went so far as to retire, knowing as undefeated champion, he could continue touring in his stage show “Gentleman Jack”.

The vacant championship was contested by Peter Maher and Steve O’Donell – a bout originally intended as a supporting fight to the long-awaited Fitzsimmons-Corbett tussle. Maher won and, on February 21st, 1896, was forced to meet Fitz at Langtry, Texas. The Cornishman had been frustrated long enough and was not about to let the title slip. Within just 85 seconds of the start of the fight, Maher was knocked unconscious and Bob Fitzsimmons suddenly found himself Heavyweight Champion of the World.

In June, Fitz set off for Southampton on a victory tour that would take in many of England’s most celebrated music halls. Celebrations, however, would be decidedly short-lived. In the autumn, Fitz returned to the States only to find “Gentleman Jim’ had come out of retirement. As the rules then stood, the heavyweight crown automatically reverted to the undefeated Corbett. And again, there being no controlling body in those days to stop a champion doing more or less as he pleased, the American chose to fight other men.

Not until March of the following year would Corbett finally consent to bring the saga to an end. At almost a stone heavier than his 11 stone 3 pounds opponent, the champion was the overwhelming favourite of both the 4,000 strong Carson City crowd and the sporting press.

The early rounds of their epic battle seemed to justify that assessment. Corbett proved himself by far the better technician, and Fitz was left absorbing a punishing weight of well-timed blows. In round 6, indeed, many believed the Cornishman had blown his chance, when a dominant champion sent him to the deck.

It used to be said, however, that “Ruby Robert” was never more dangerous than when hurt. At the count of nine, Fitz got up and came back fighting. Another bruising eight rounds would follow.

Corbett remained the more skilful boxer, but Fitz reverted to a well-worn strategy. The Cornishman was famous for his devastating body-punches, and near the end of rounds his beloved second wife, Rose, could be heard screaming out: “Hit him in the slats!”

Slowly but surely, the strategy was taking its toll. In the 14th, champion and challenger stood toe to toe, when Fitz suddenly unleashed a staggering blow to the American’s solar plexus. It would be the last punch either man would have to take. Corbett went down with such a groan the world was left in zero doubt it had a new heavyweight champ.

Thirty-eight thousand dollars richer as a result of the victory, Rose insisted her husband would never fight again. Public engagements and a tour of the U.S. theatres in a two-act melodrama entitled “The Honest Blacksmith” kept Fitz out of the ring for the next two years. But by now the fight game was in his blood, and he had to return. Inactivity, plus an opponent twelve years his junior and over four-and-a-half stones heavier, combined to rob Fitz of his heavyweight crown after 11 gruelling rounds. Still, he was not discouraged. Despite breaking both his hands in a re-match with the new champion, the mammoth James -The Boiler-Maker” Jeffries (who, though defeating him twice, became one of Fitz’s greatest friends), the Cornishman went on to take a third world title in 1903. Then over 40, it came to a points victory for the newly created light-heavyweight division.

The first fighter to win three separate world titles under Queensbury Rules, the first over 40 to take a world crown, the lightest ever heavyweight champ, the first British boxer ever to become the undisputed conqueror of that most prized of all divisions – Bob Fitzsimmons’ career makes a Who Did What of World Boxing? in itself.

Amid all the high moments, there was no shortage of controversy, of course. On one famous occasion, Fitz is said to have been “taken for a sucker” by the legendary marshal Wyatt Earp, for example. Earp liked to referee, and in an allegedly “fixed” fight, he disqualified Fitz for a low blow only he had seen. Buckling on his gun-belt in case anyone fancied arguing, the marshal awarded the purse to Fitz’s unconscious opponent “Sailor Tom” Sharkey.

On two other occasions, Fitz came close to retiring following the deaths of opponents. But inquests fortunately concluded that neither of the men – Con Riordian and Con Couglin – stepped into the ring in any fit condition to fight. Outside boxing, the Cornishman’s life was just as colourful. Though no Adonis, he married four times – losing Rose, the beloved second wife he stole off his manager, divorcing two others and being outlived by the last. Ending up broke, Fitz claimed he had been “swindled” by unscrupulous moneymen; but lavish spending on the women in his life cannot have helped. Over $300,000 went on jewellery, clothes and voice tutoring for one ex-wife alone.

Little wonder then, that he fought on into his fifties -and like too many, sadly, well past his prime. The great man was just 54, in fact, when on October 22nd, 1917, a severe attack of lobar pneumonia drew a premature curtain on life. The grand old showman – who, at his peak, often wrestled a tame lion or bear in training to entertain spectators – was buried in the Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, before over 3,000 friends and admirers. In 1946, just 200 feet away, they buried Jack Johnson – making it the only site on earth where two heavyweight champs have found the same final resting place.