What I do mosley is what used to Bee out of my own memory what we may never see again as Thing are altered altogether

So wrote Alfred Wallis, arguably the strangest and one of the most original of all Cornish painters in response to a note he’d received (and that must have surprised him), to explain what he was trying to do in his work. This was in April, 1935, by which time he had become recognised by fellow painters as a rather special sort of artist: and in an echoing sort of way – with all the bad spelling and the equally bad grammar – the little letter he laboriously wrote, uncannily mirrored all that was special in his paintings. Childlike but not childish, and supremely honest…. Never before nor since has there been a painter quite like Wallis. He didn’t pick up a brush until he was seventy, but in the seventeen years that were left to him, until he died in a Cornish workhouse, he painted hundreds of pictures; and among those that remain to us in galleries not only in England but across the world. there are many looked upon as minor masterpieces. Especially by painters: for Wallis. from the most un-artistic of beginnings. became a painters’ painter. and the most improbable inspiration for mariy of them…. If birth is the only acceptable qualification, Wallis was not Cornish. He was born in Devonport (“on the day of the fall of Serverserpool Rushan War”, he once wrote: his father was fighting in the Crimea at the time), but most of his life, and certainly all his painting life, was spent in Cornwall. And the sea was ever near. He was a ten-year old cabin boy on boats, deep-sea ones, which fished for cod off the cold, foggy banks of Newfoundland; and then, when a young man, sailing out of Newlyn and St. Ives, he fished kinder inshore waters off Cornwall. teaming then with seemingly endless shoals of herring, mackerel, and pilchard. They were days he would never forget. In due course, however, he left the sea. To get married: a widow twenty years older than he was, a kindly but dominating woman from all accounts, and they started up a rag-and-bone business in St. Ives, which Wallis grandly named his “Marine Stores”. He got himself a cart. and first a donkey and then a horse called Alfred. and together they would clop their way to Penzance to sell their scrap, old bedsteads and the like. with Alfred wearing an old sea captain’s cap. Even then. he was solitary man, and this trait in his character never changed: but at the age of seventy most everything else did. Alfred Wallis decided to paint…. And he painted on just about everything and anything that came to hand. Odd bits of cardboard and mis-shapen bits of wood, old calendars and shoe boxes, ginger-jars and jugs, dinner plates and cereal packets; and even upon his old fire-side bellows – one of my favourite pieces of his which I saw a couple of years’ back at the splendid Tate in St. Ives. No painter has ever filled such wayward shapes as instinctively as he did, and beyond a peradventure, no painter has relied upon old ship’s paint which Alfred, no man to throw anything away, presumably had stored in his old store-house.

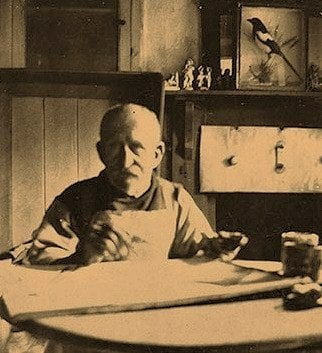

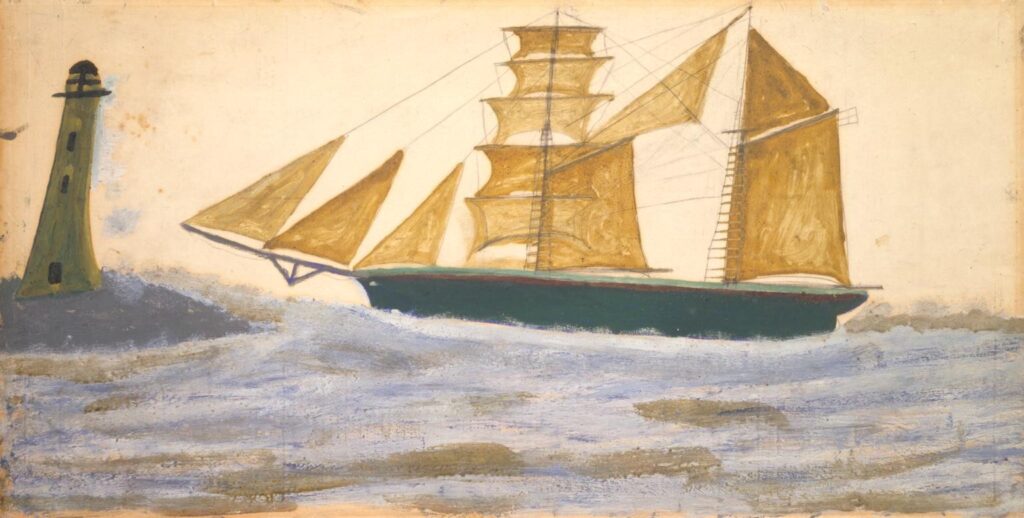

However, for all of Wallis’ frenetic and compulsive painting, and he turned out scores in every week, not many remain to us. Not least because he used to take many of them to the local baker and exchange them for pasties: and the baker, or so it said, used them to fire-up the oven for the next day’s baking. . Not that anyone should blame the baker, for by this time the introverted Wallis had become even more eccentric. His wife had died, he was becoming increasingly deaf. he was as stubborn as he had always been, and his sense of persecution bore ever more heavily upon him. He was plagued in his mind not only by children who had always taunted him, but by the wireless, and voices which came down the chimney accusing him of being a Catholic – and he a devout Salvationist, like his wife before him, who together stood, Sunday after Sunday, on the slipway at St. Ives and joined in the Salvation Army’s stirring hymns…. So there, in St. Ives, was this reclusive man. Alone and lonely in his lonely cottage, with his thoughts and memories and his devils. Until one day he had a further eccentric thought…. Once a year, in those days, the “real hartists”, as once Wallis called them, opened their studios in St. Ives to show off their work and old fishermen’s lofts became places of glowing colour: and it was upon such a day that Alfred decided to put on a show of his own work. On the pavement, outside his little house: and he sat there, surrounded by his paintings. Quite by chance (and isn’t this the way of artistic matters), two distinguished painters strolled along the street, and they were amazed by what they saw. Later, they recalled that Wallis to them looked like Cezanne: huddled at a table outside his house, small, wizened, stubbled, his paintings all about him. “Are you showing pictures?” they asked. “If you’ve a mind to call ’em pictures,” Wallis said. “Are you selling them?” “I don’t want to sell,” said Wallis. -But I’ll give ‘ern to ee.” Whatever else passed between the “hartists” and the artist, I have no idea, and nor has anyone else. I do so hope that those two painters went into his cottage and saw the very special eye that Wallis had. An untutored eye, like the eye of a seagull, looking down on embracing little harbours, much more secure that they could ever have seemed from a tumbling sea. And I hope, too, that they may have seen another favourite Wallis picture of mine, and the dark, sad humour of him. It’s a painting of a Cornish terrace, but one house in the string is tiny. It’s the house of a man whom Wallis hated. And then there are the lighthouses that you think a child could draw, cylinders with little bonnets on top; and childlike ships (but the rigging always right); and huge fish swimming around them, sharks and whales as big as those described by old seafarers to a wide-eyed cabin-boy who believed every tall tale they told. But not much colour. “i do not put collers what do not Belong. Their have Been a lot of paintins spoiled by puttin Collers where they do not Blong….”

Alfred Wallis died, in 1942, in Madron Workhouse, and he lies now in a sloping cemetery in St. Ives, a monumented place overlooking the sea. His own resting place is glazed with tiles by Bernard Leach, and a simple inscription is upon it: “Alfred Wallis. Artist and Mariner”. Not many tributes were paid to Alfred Wallis in his own lifetime. They were to come later and none more graceful than this: “In homage to the artist on whom Nature bestowed the rarest of gifts. Not to know that he is one.”