It has often been said that the Church of England is rich in eccentrics, and one of these must surely have been Robert Stephen Hawker, Vicar of Morwenstow in Cornwall from 1834 until his death in 1875. A legend in his time, Hawker was an extraordinary mixture of flamboyance, superstition, and sound practical Christianity.

He was born in Plymouth in 1803, and when he was thirty, he came to Morwenstow with his wife, Charlotte, twenty-four years his senior. Despite the disparity in age, it proved to be a happy marriage, he was devoted to her until her death thirty years later.

The first sight of Morwenstow must have unnerved the new incumbent and his wife, for there are few parishes in England so wild, remote and desolate. The Norman church and vicarage lie buried deep in a wooded gorge almost hidden by gaunt cliffs towering high above the valley. The sea, relentlessly pounding on the rocks below, is rarely calm, and in the days of sail the whole coast stretching from Hartland to Padstow was a seaman’s nightmare, a graveyard of ships…. “From Padstow Point to Lundy Light is a wat’ry grave by day or night”. Westerly gales of the utmost ferocity would sweep in from the Atlantic, and the force of the wind was often such that spray would be blown ten miles inland to Holsworthy in Devon.

But Hawker grew to love his church, set so sturdily in its remote valley, its tower a comforting landmark to passing ships – his imagination dwelling avidly on the macabre beauty of the place. He described the wind as “howling in my chancel like a lion waiting for its prey”, and heard “in every gust of the gale a dying sailor’s cry”, being firmly convinced that the valley was haunted by the ghosts of drowned men.

Morwenstow churchyard is the last resting place of fifty seamen carried there by Hawker from the foot of the cliffs, most of the bodies having been hacked to pieces on the rocks. The mental and physical anguish of the vicar can scarcely be imagined, but he strove to overcome his revulsion for this grim task in order to fulfil what he considered was his duty to give the pitiful remains a Christian burial.

The most tragic wreck was that of the sailing ship Caledonia in 1842, homeward bound for Odessa. Caught in a violent storm the vessel was dashed to pieces on the rocks below the vicarage. Hawker describes the scene: “We made a temporary bier of broken planks and laid thereon the corpses… my people followed as bearers and in sad procession we carried our dead up the steep cliff.”

The bodies were buried against the churchyard wall, and over the captain’s grave Hawker placed the figurehead of the Caledonia. The wooden figure with upraised sword and shield still stands in the churchyard, dazzling white against the sombre dark cypresses.

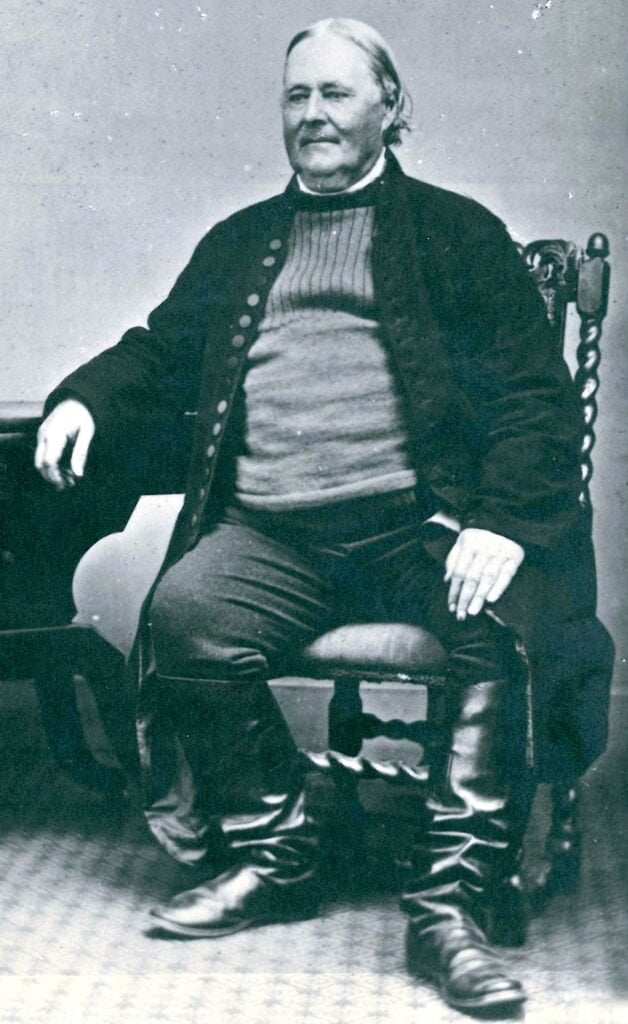

This dreadful incident was to be repeated many times with varying degrees of horror, and on each occasion, Hawker, lantern in hand, and clad in fisherman’s jersey, seaboots and cassock, would set off across the fields in the teeth of the storm to render what aid he could or, if human aid was past, to bear away the remains in wicker baskets for burial.

He wrote: “All I have read comes back upon the mind – until the body is interred the soul can win no rest….”

As the years passed, he became even more prone to morbid imaginings, spending long hours in a driftwood hut on the cliffs scanning the skies for approaching storms. After Charlotte died these eccentricities increased, but at no time did his innate goodness and warmth of heart become diminished by these mental disturbances, and when a year after Charlotte’s death he resolved to re-marry, all Morwenstow rejoiced.

His bride, Pauline, was a Polish girl of twenty-three. When they first met, she was employed as a governess to the children of a Yorkshire parson convalescing in the village. Hawker became friendly with the family, and his liking for Pauline quickly deepened into love. She too was attracted to him, for despite his peculiarities Hawker was a man of considerable charm.

This marriage proved as successful as the first. Pauline was attractive, lively, and intelligent, the perfect companion for such an introspective man. She loved him dearly, declaring that she “would rather spend ten years with Hawker than a lifetime with any other man”. Three daughters were born to them, and their happiness was complete.

After his re-marriage Hawker’s idiosyncrasies tended to lessen, but he still indulged in somewhat peculiar behaviour such as wearing a yellow blanket with a hole cut out for his head while riding a mule on his pastoral duties, he maintaining that the early Christian fathers had done the same, and allowing his many cats to roam freely around the church during services. On one occasion a cat caught a mouse in the choir stalls and was immediately excommunicated by the vicar! He allowed his dog to sleep undisturbed on the altar steps and had a deep affection for his pig who also had the run of the church.

One is irresistibly reminded of another eccentric person who lived two hundred years before Hawker across the Tamar in Devon… Robert Herrick, lyric poet, and vicar of the moorland parish of Dean Prior during the reign of Charles I. He too loved animals and, like Hawker, welcomed them to his congregation, nonchalantly preaching at Harvest Festivals while his two pigs ate the melons and apples stacked beneath the pulpit. He, like Hawker, rode many miles across his equally remote parish, not on a mule, but on a more conventional horse.

But here the comparison ends, for where Hawker was inclined to morbidity and introspection, Herrick was a jovial extrovert, delighting in worldly pleasures – pretty women, wine, country festivals, village weddings, spring-time and harvest, ever conscious of the transience of this mortal life and determined to enjoy it to the full.

Hawker was now rapidly ageing, the care and responsibility of a wife and a growing family, combined with the harsh environment of Morwenstow, imposing an intolerable burden upon him. In August 1875, a clot of blood settled in his arm and a few days later he died.

He is buried at Plymouth and on his grave are the words: “I would not be forgotten in this land.”

His wish is granted. For well over a century he is still remembered as a writer, a minor poet, and the author of Trelawny – The Song of the Western Men, and the instigator of Harvest Festivals as we know them today, as opposed to the more pagan type favoured by Herrick. But above all, Hawker is remembered simply as Hawker of Morwenstow; a man of faith and unflinching courage, one of the long lines of English eccentrics to whom, down the centuries, we owe so much that is good.