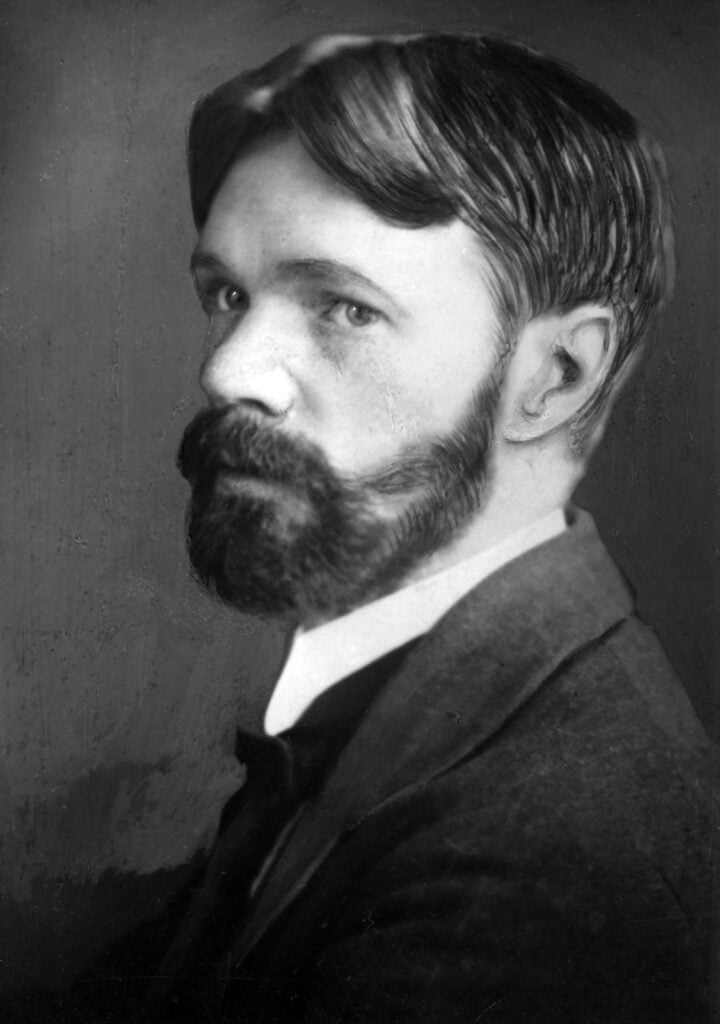

The tortuous, tormented, ambivalent life of D.H. Lawrence – best known for Lady Chatterley’s Lover, nowhere near his best book but by far the most notorious – had a while in Cornwall: and it was a time in which he suffered greatly, and during which he wrote some of the nicest and nastiest things about the Cornish that have ever been written.

All of them in their shifting way (and Lawrence was much a man of shifting moods) invested with much truth. Some, the Cornish will like; others, they won’t. But Lawrence was a man who wrote as he felt at the moment, and his vivid mind took no account at all of the fact that what he said today should be challenged tomorrow. His mind was too mercurial to bother about things like that.

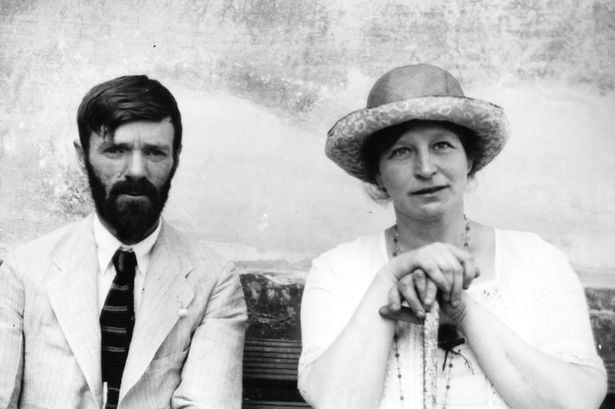

Actually, with hindsight, his coming to Cornwall was a disaster waiting to happen. He and his wife Frieda, German-born of an aristocratic German family, came to Cornwall in the second winter of the First World War. It was hardly the best time to come, and it wasn’t their first choice.

They had this idea of forming a nucleus of a colony of people who would live together in such a way as to show the world where the world was going so fearfully wrong, and their first choice was Florida. That became clearly impossible, so Cornwall became the second choice. To the Lawrences, the place was secondary, the ideal was the thing. The commanding, elusive, consuming dream was all……

In the dying December days of 1915, Lawrence wrote this letter to a friend:

I want so much that we should create a new spirit, a unanimity between a few of us who are desirous that we should add our lives together to make one tree. Each of us free and producing in his separate fashion, but all of us together forming one Spring – a unanimous blossoming. It needs that we should be one in spirit: that is all. What we are personally is of second importance. We go to Cornwall on Thursday.

Lawrence and Frieda took a friend’s cottage at Porthcothan, near St. Merryn, and they adored it. After a mere week, Lawrence was enthusing about it:

I love being here in Cornwall: it’s so peaceful. So far off from the world. The world has disappeared for ever – there is no world anymore. Only here, and a fine thin air which nobody and nothing pollute.

Lawrence liked the Cornish people, too:

There is a rare quality of gentleness in some of them – a sort of natural flowering gentleness that I love.

This benevolence, however, didn’t last long. Within a month, the Cornish people had become “detestable”, and they were “like insects gone cold, living only for money. They are foul in this. They all ought to die”. And yet in this self-same letter, Lawrence cheerily admitted: “Not that I have seen very much of them. I’ve been laid up in bed.”

However much Lawrence, though, wavered in his thoughts of people, he never once lost his love and admiration of the Cornish landscape:

The shore here is absolutely primeval: those heavy black rocks, like solid darkness, and the heavy water like the first twilight breaking against them and not changing them. It is really like the first craggy breaking of the dawn in the world.

That was from St. Merryn: but when in the spring of 1916 the Lawrences moved to a cottage at Zennor he found the landscape there just as magical: It is a most beautiful place nestling under high, shaggy moor-lands, a big sweep of lovely sea beyond , such lovely sea, lovelier than the Mediterranean…. All gorse now, flickering with flowers; and then it will be heather; and then hundreds of foxgloves…. Lambs skipping and hopping like anything, and seagulls fighting with the ravens, and sometimes a fox…. It is the best place I have been in. We will live here for a long time – very cheaply.

Cheap, the cottage the Lawrences rented certainly was: five pounds a year. It was called Higher Tregerthen and it lay almost touching that improbable plain of grass just over the hill from the mermaid-ended pews of the parish church, and so unlike the shaggy boulder-strewn hills that Lawrence had written about.

Everything seemed well. Lawrence and Frieda rowed, as they always did, of course; the local people hardly knew what to make of them – something which was hardly surprising, for the Cornish in those days ever found it difficult to some to terms with writers, painters and the like; but Lawrence forged one or two deep friend-ships, and his view of the Cornish people mellowed.

Never more so than when he was summoned to the military barracks in Bodmin to be medically examined for service in the army. (He was, in fact, exempted.)

There, for a single day, he was thrown into the company of a group of ordinary Cornishmen who, like him, had been called to the Colours: and he saw them as he first had – gentle. These Cornish are most unwarlike -soft. gentle, peaceable, ancient. No men could suffer more than they at being conscripted. Yet they accepted it all: they accepted it, as one of them said to me, with wonderful purity of spirit. And 1 could howl my eves out over him.

So, it was back to Zennor for Lawrence, and to the cottage that so innocently overlooked the sea. But it was a sea in those days prowled by German submarines, and Frieda was German-born and given to singing German songs, and the Lawrences were as care-less about drawing their curtains as they were careless about most other things, and tongues (as they tend to do in close communities) began to wag.

A German lady, a threatening sea, lights at night from sea-seeing windows, strange strangers. It didn’t need much for all of it to come together. However absurd it all was….

And in the October of 1917, the absurdity became fact, and Lawrence wrote in panic and disbelief:

The Police have suddenly descended on the house, searched it, and delivered us notice to leave by next Monday. Why, I know not, I cannot even conceive how I have incurred suspicion. We are as innocent of pacifist activism, let alone spying of any sort, as the rabbits in the field outside.

Within three days the Lawrences packed and left:

to live “in an unprohibited area, and report to the Police. It is very vile”.

So, D.H.Lawrence’s Cornish idyll ended; in bitterness and non-understanding and far from the thought he first had about Cornwall, “I shall stay here for a long, long time,” he had said.

But isn’t that the way of the true artist? Not only to be understood in their own time, but to be totally misunderstood….